Archaea can be picky parasites

A parasite that not only feeds of its host, but also makes the host change its own metabolism and thus biology. NIOZ microbiologists Su Ding and Joshua Hamm, Nicole Bale, Jaap Sinninghe Damsté and Anja Spang have shown this for the very first time in a specific group of parasitic microbes, so-called DPANN archea. Their study, published in Nature Communications, shows that these archaea are very ‘picky eaters’, which might drive their hosts to change the menu.

Dutch translation can be found below

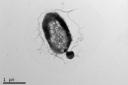

Electron microscopy showing the parasitic Ca. Nha. antarcticus: the small circular shape, attached to its host, Hrr. lacusprofundi. Image Credit: Joshua N Hamm

Archaea are a distinct group of microbes, similar to bacteria [see box]. The team of NIOZ microbiologists studies the so-called DPANN-archaea, that have particularly tiny cells and relatively little genetic material. The DPANN archaea are about half of all known archaea and are dependent on other microbes for their livelihood: they attach to their host and take lipids from them as building material for their membrane, their own outer layer.

Picky eaters

So far, it was thought that these parasitic archaea just eat any kind of lipids from their host to construct their membrane. But for the first time, Ding and Hamm were able to show that the parasitic archaeon Candidatus Nanohaloarchaeum antarcticus does not contain all the lipids that his host Halorubrum lacusprofundi contains, but only a selection of them. “In other words: Ca. N. antarcticus is a picky eater”, Hamm concludes.

Archaea, bacteria and higher organisms

Archaea are single celled organisms that were long believed to be a specific group of bacteria. Similar to bacteria, they do not have a nucleus with dna, or other organelles within their cells. As of the 1970’s, however, microbiologists no longer consider archaea bacteria, but classify them as a separate domain in all life forms. So, now we have archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotes, the latter including all animals and plants, that have a nucleus with genetic material in their cells.

Host responds to parasite

By analyzing the lipids in the host with or without their parasites, Ding and Hamm were also able to show that the host responds to the presence of their parasites. The hosts change their membrane, not only which types of lipids and the amounts of each type that are used, but also modifying the lipids to change how they behave. The result is an increased metabolism and a more flexible membrane that is also harder for the parasite to get through. That could have some consequences for the host, explains Hamm. ‘If the membrane of the host changes, this could have an impact on how these hosts can respond to environmental changes, in for example temperature or acidity.”

Game-changing new technique

The game-changer in this microbiological research was the design of a new analytical technique by Su Ding at NIOZ. Thus far, to analyze lipids you needed to know what lipid groups you were looking for and target them in the analysis. Ding designed a new technique in which he can look at all lipids simultaneously, also the ones you don’t know yet. “We probably wouldn’t have been able to see the changes in the lipids if we had used a classical approach, but the new approach made it straightforward,” says Hamm.

New insight

The microbiologists are very excited about these new findings. “Not only does it shed a first light on the interactions between different archaea; it gives a totally new insight in the fundamentals of microbial ecology”, Hamm says. “Especially that we’ve now demonstrated that these parasitic microbes can affect the metabolism of other microbes, which in turn could alter how they can respond to their environment. Future work is needed to determine to what extent this may impact the stability of the microbial community in changing conditions.”

Another example of the parasitic Ca. Nha. antarcticus attached to its host, Hrr. lacusprofundi. Image Credit: Joshua N Hamm

Een parasiet die niet alleen van zijn gastheer leeft, maar er ook nog eens voor zorgt dat diens stofwisseling verandert. Een team van NIOZ-microbiologen heeft dit voor het eerst aangetoond bij een specifieke groep parasitaire microben, de zogeheten DPANN archea. Het onderzoek, gepubliceerd in Nature Communications, laat zien dat deze archea nogal kieskeurige eters zijn, wat er mogelijk voor zorgt dat de gastheer het menu verandert.

Archea vormen een aparte groep van microben, die lijken op bacteriën (zie kader). Het onderzoeksteam, bestaande uit Joshua Hamm, Su Ding, Nicole Bale, Jaap Damsté en Anja Spang, doet onderzoek naar DPANN archea, die zeer kleine cellen hebben en releatief weinig genetisch materiaal. Deze DPANN archea vormen ongeveer de helft van alle bekende archea, en zijn afhankelijk van andere microben om te overleven: ze hechten zich aan hun gastheer en nemen lipiden van de gastheer op, als bouwstenen voor hun membraan, hun eigen ‘jas’.

Kieskeurige eters

Tot nu toe werd gedacht dat deze parasitaire archea gewoon alle lipiden van hun gastheer opnamen om hun membraan van te maken. Maar onderzoekers Ding en Hamm hebben nu voor het eerst aangetoond dat een specifieke parasitaire archeon, Candidatus Nanohaloarchaeum antarcticus, niet alle lipiden bevat die zijn gastheer Halorubrum lacusprofundi bevat, maar slecht een selectie ervan. “Met andere woorden: Ca. N. antarcticus is een kieskeurige eter,” concludeert Hamm.

Archea, bacteriën en hogere organismen

Archaea zijn eencellige organismen waarvan lang gedacht werd dat het een specifieke groep bacteriën was. Net als bacteriën hebben ze geen kern met dna of andere organellen in hun cellen. Vanaf de jaren zeventig van de vorige eeuw beschouwen microbiologen archaea echter niet langer als bacteriën, maar classificeren ze hen als een apart ‘domein’ binnen alle levensvormen. Nu hebben we dus archaea, bacteriën en eukaryoten, waaronder alle dieren en planten, die een kern met genetisch materiaal in hun cellen hebben.

Gastheer reageert op parasiet

Door te analyseren welke lipiden de gastheer bevatte in aan- en afwezigheid van hun parasieten, konden Ding en Hamm ook aantonen dat de gastheer reageert op de aanwezigheid van de parasiet. De gastheer past zijn membraan aan: het soort lipiden en de hoeveelheden ervan verandert. Ook worden bepaalde lipiden zelf aangepast, zodat hun werking verandert. Het resultaat is een verhoogd metabolisme van de gastheer, en een meer flexibel membraan waar de parasiet ook lastiger doorheen kan dringen. Die verandering kan consequenties hebben voor de gastheer, legt Hamm uit. “Als het membraan van een microbe verandert, kan dat invloed hebben op hoe goed die microbe kan omgaan met veranderingen in zijn leefomgeving, bijvoorbeeld in temperatuur of zuurgraad.”

Nieuwe techniek is game-changer

De ontwikkeling van een nieuwe analytische techniek door Su Ding bleek een game changer voor dit microbiologische onderzoek. Tot nu toe moesten wetenschappers bij het analyseren van lipiden precies weten welke groep van lipiden zij zochten, om deze in de analyse boven water te krijgen. Ding ontwierp een nieuwe techniek, waarmee de onderzoekers naar alle lipiden tegelijk kunnen kijken – ook de onbekende. “Als we de klassieke aanpak hadden gebruikt, hadden we waarschijnlijk de verandering in lipiden bij de gastheer niet gezien. Maar met de nieuwe aanpak was het overduidelijk.’

Nieuw inzicht

De microbiologen zijn heel enthousiast over deze nieuwe bevindingen. “Het werpt niet alleen een nieuw licht op de interacties tussen verschillende archaea; het geeft een totaal nieuw inzicht in de fundamenten van microbiële ecologie", zegt Hamm. “Vooral dat we nu hebben aangetoond dat deze parasitaire microben het metabolisme van andere microben kunnen aanpassen, wat er vervolgens voor kan zorgen dat die gastheer-microbe anders op de omgeving reageert. In vervolgonderzoek moeten we gaan kijken in hoeverre dit effect heeft op de stabiliteit van microbiële populaties in veranderende omgeving.”