How do migratory birds find their way

Bird migration is a fascinating phenomenon. Each autumn, millions (if not billions) of birds migrate through our country to spend the winter in more southern regions. After months of absence, they then return the next spring to breed and raise their young in our country or further north.

Introduction

How do inexperienced birds, that are still to make their very first migration, know where to go? Is the route (the direction and distance) coded in their genes, or do birds learn the route by following experienced adults. Very little is known about this. Yet, finding an answer to this question is very important when we want to understand how fast migratory birds can adjust their migration routes when their environment changes. Change may mean that areas that they once used during migration or in winter, become unsuitable, but change may also be positive, when areas become more suitable because of improved protection.

Why is this important to know?

The extent to which migration routes are shaped by genetic versus environmental factors will determine how fast migratory species can adjust their migration routes to a changing world. If migration routes are primarily shaped by genes, the rate of adaptation depends on the amount of genetic variation as well as generation time. For long-lived species with long generation times, like spoonbills, natural selection of suitable 'migration-genes' through 'survival of the fittest' is a rather slow process. If young birds learn the migration routes from adult conspecifics, the rate of adaptation is expected to be relatively quick, as young birds will not follow migration routes that are no longer suitable, since the adults that followed these routes will not have survived. Besides using social information, young birds also experience food availability and weather conditions themselves, at stopover sites and during migration, which may affect their decision to continue migration or stay at a site, or to change the course of migration, which may lead to faster adaptation of migration routes.

Implications for conservation

This study will teach us about the factors that shape migration routes of young spoonbills, which will affect the capacities and constraints of spoonbills in particular, and migratory birds in general, to adjust their migration routes to changes in their environment. In addition, tracking spoonbills with transmitters, as well as with colour-rings, gives us more insight into (changes in) the key areas that are used by spoonbills throughout the annual cycle and how site use is associated with survival. This information can be used to better protect the wetlands (e.g. estuaries, tidal basins, ricefields, salt ponds) that are of key importance for spoonbills, and likely also for many other water- and shorebirds.

What do we know?

Some studies performed in captivity showed a genetic basis for the direction in which birds fly, and for the period during which they exhibit ‘zugunruhe’. ‘Zugunruhe’ is a term for the restless behaviour that migratory birds display when they are kept in captivity during the period that their wild conspecifics are migrating. In contrast, studies that followed wild birds with transmitters revealed that the environment plays an important role in shaping the migration routes of young, inexperienced, birds. For example, the migration routes of young Honey Buzzards are strongly shaped by wind direction and wind speed during migration, while young White Storks survive better, and young Lesser Spotted Eagles find more suitable migration routes, when they migrate together with experienced adults.

Aim of the project

Until now, the genetic basis of migration distance and direction has only been studied in the lab, while the importance of environmental factors has been studied in populations with unknown genetic variation in migration distance and direction. Therefore, we do not know to what extent the individual variation in migration routes that we observe in the wild is shaped by genetic variation or by variation in the environment that young birds experience during their first southward migration. Environmental variation includes the role of social information from experienced adults, food availability, geographical barriers (many birds avoid crossing large water bodies and mountain ranges) and weather conditions. This VENI project aims to contribute to closing this knowledge gap by studying in concert the role of genetic and environmental factors in shaping individual migration routes, using the Eurasian Spoonbill as a model system.

Why spoonbills?

The Netherlands harbor more breeding pairs of Eurasian spoonbills than any other country in Europe, with 3200 breeding pairs in 2018. Because the population has been monitored for over 30 years by annually counting the number of nests and colour-ringing juvenile birds, we have been able to accurately quantify how population size, survival rates and migration routes have changed over the years. In a period during which the population size has increased six-fold (from 500 in 1990 to 3200 breeding pairs in 2018) survival has decreased, presumably because of increased competition for food, with survival decreasing most strongly in first-year birds. We also found that the survival of birds wintering in Europe was consistently higher than that of West-African wintering birds, and that in the period 2006-2009, also the breeding success of European winterers was higher. This indicates that for spoonbills, staying in Europe to spend the winter (instead of migrating further south and crossing the Sahara to spend the winter in West Africa) would be the best choice. However, despite the higher survival and breeding success of European wintering spoonbills, still half of the population migrates to West Africa. This raises the following questions: why are there still spoonbills that migrate to West Africa and why are not all spoonbills staying in Europe to spend the winter? Why is the shift towards more northern wintering areas not going much faster? To answer these questions, we need to understand the role of genetic and environmental factors affecting individual migratory decisions. How do we investigate the importance of genetic and environmental factors in shaping individual migration routes?

We will follow young spoonbills on their first southward migration using two methods:

- the conventional method of colour-ringing juvenile spoonbills and observing them along the flyway

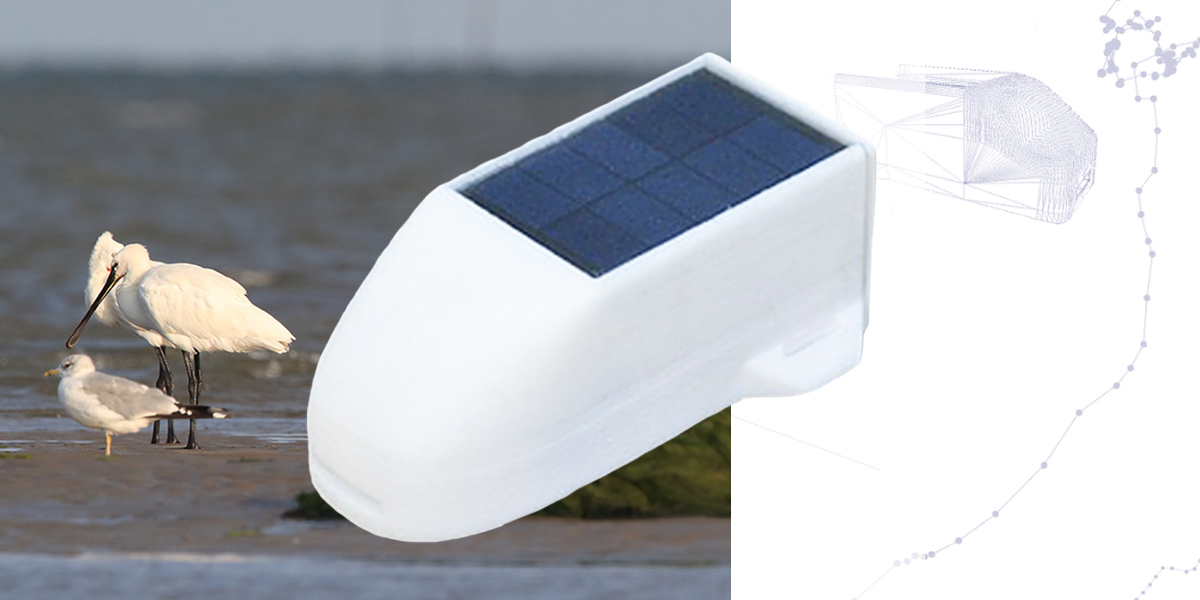

- equipping juvenile spoonbills with sophisticated GPS-GSM trackers.

These trackers collect very detailed information on their whereabouts (a GPS position is registered every 10 minutes) as well as about their behavior (acceleration data are collected together with each GPS position).

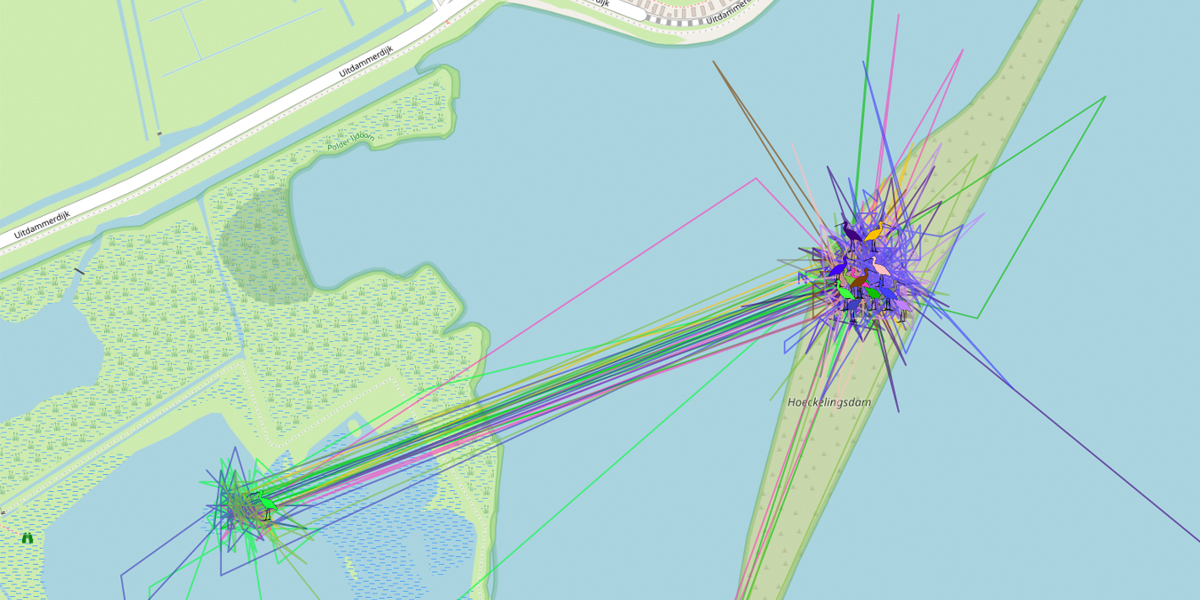

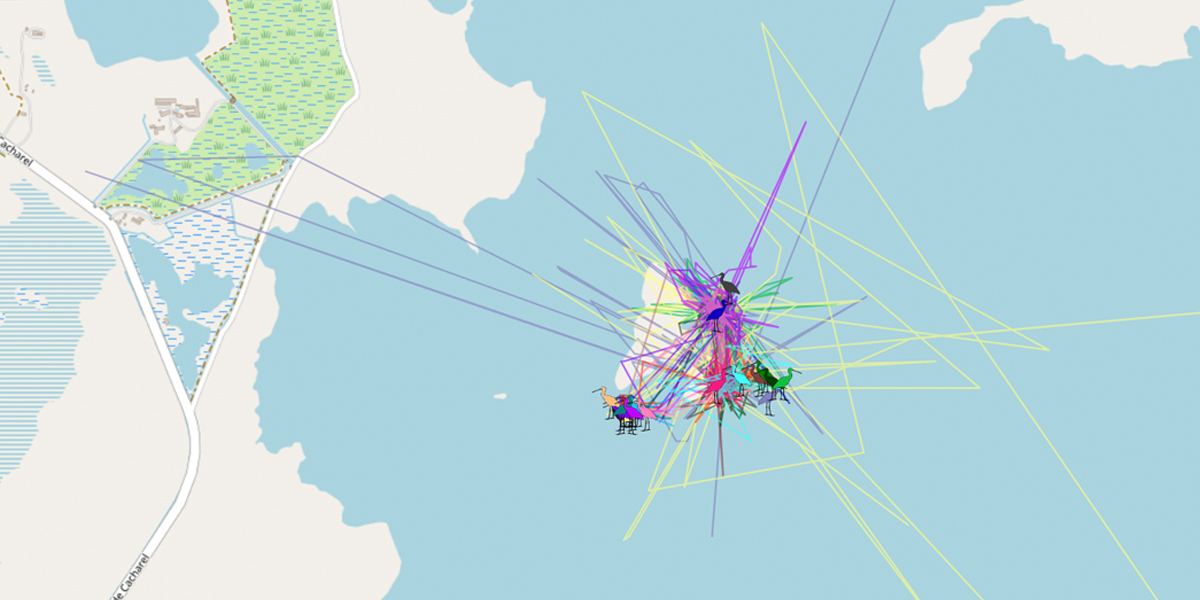

The additional advantage of the GPS-tracked juveniles is that they can be followed online, which allows observers to go into the field and search for the birds to collect information on their (social) environment (see below). We will follow juveniles born in The Netherlands (Schiermonnikoog) and in southern France (the Camargue); two populations that exhibit contrasting levels of variation in migration distance and direction.

To determine the importance of genetic factors, we collect information on the genetic relatedness of individuals, by performing observations in the colony to determine who are the parents of which chicks. Combined with information on the migration routes of parents and their chicks, siblings, nephews and nieces, this enables us (through quantitative genetic analysis) to estimate the contribution of genetic (versus unexplained, i.e. environmental) variation to the observed individual variation in migration routes.

In addition to information about genetic relatedness of individuals, we collect information on the environment that young spoonbills experience during early life. We use automated data from weather stations to investigate the importance of wind conditions and temperature, but to investigate the importance of habitat quality and social information, we need ground observations on intake rates, habitat type, prey types, and the presence of other spoonbills, and whether these are juveniles, adults, and if there are colour-ringed individuals among them.

Veni project

What do they know, what do they learn, and how does this affect their ability to cope with ecological change?

We need your help!

For the collection of data about the environment that the tracked juvenile spoonbills experience prior and during their first southward migration, we strongly rely on data collected by citizen scientists. Read here for more information on how you can contribute to this project!

Follow juvenile spoonbills

from France

Follow juvenile spoonbills from The Netherlands