Inaugural lecture Jan-Berend Stuut 21 October 2021 | 'Desert dust plays a major role in our climate'

~~for Dutch scroll down~~

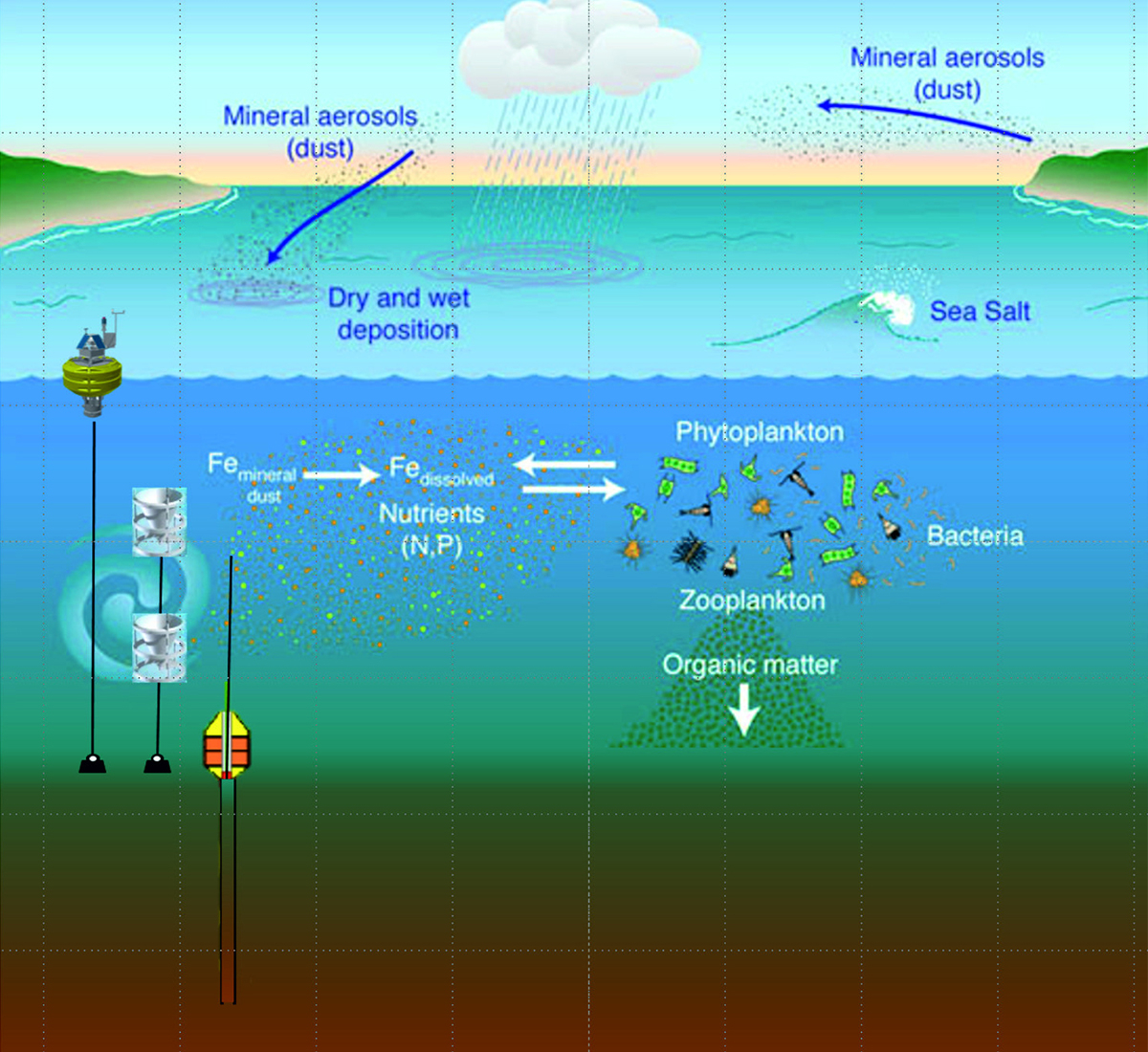

Dust leads to carbon sequestration

The relationship between dust and climate runs largely through the algae in remote parts of the oceans. "In the middle of the ocean, algae get their fresh food mainly through the air, so through dust particles. In addition to this food from the air, they also absorb CO2 from the water. When the amount of CO2 in the water drops, the ocean eventually absorbs additional CO2 from the atmosphere. In this way, through the growth of algae, fertile dust reduces the greenhouse effect”, Stuut explains.

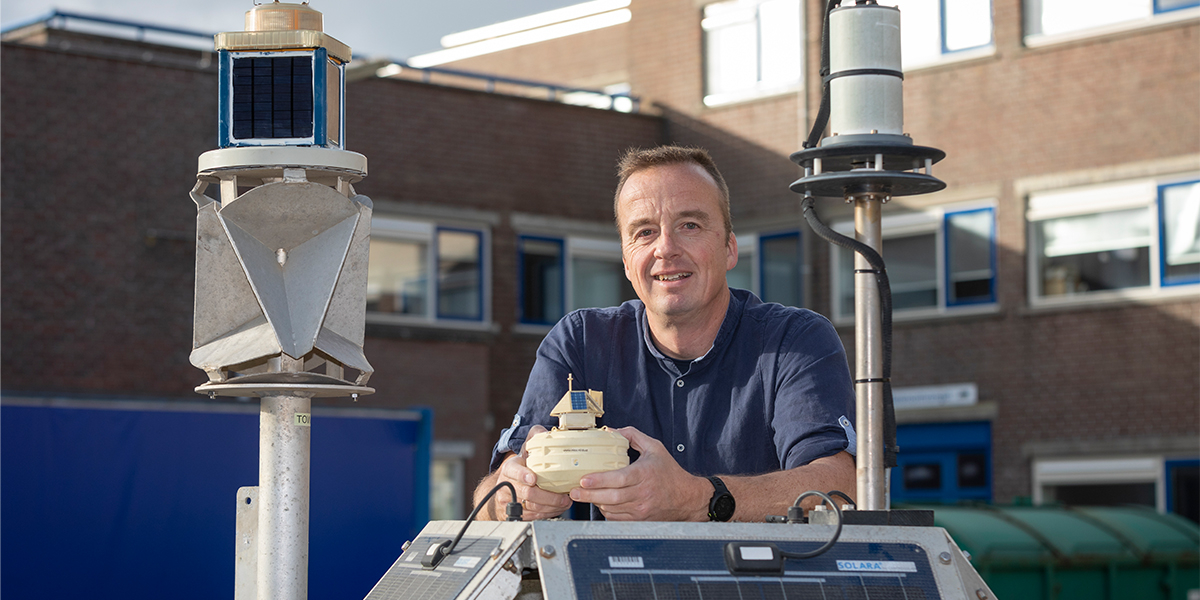

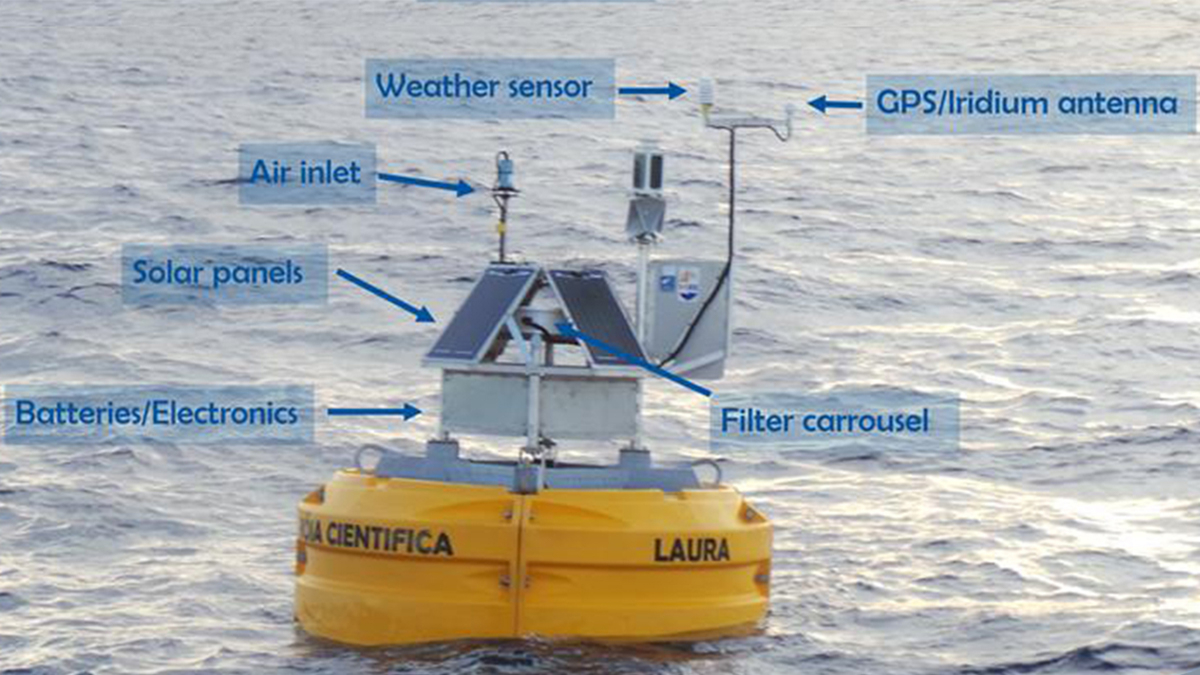

Dust buoys

For the research of Stuut's group, several so-called dust buoys have been floating on the Atlantic Ocean between Africa and South America since 2013. Shortly, these will not only catch dust, but rain as well. "The dust buoy 'Michelle' has recently been taken out of service, but on the buoys 'Carmen' and 'Laura', all named after PhD students from my group, we will soon install advanced rain gauges. Indeed, we believe that rain is essential for making nutrients ‘edible’ for the ocean's algae. Essential nutrients such as iron, nitrogen and phosphate that are stuck to the tiny grains of sand are not, by themselves, readily available to algae. Only when they are ‘pre-soaked’ for a while in a fresh and, more importantly, relatively acidic raindrop, does its chemical form change into nutrients that are useful to algae. So, if you want to know how dust fertilizes the oceans, stimulates algae growth and thereby fixes CO2, then you will also need to know how much dust ends up in the ocean with or without rainfall."

The inverse relationship between the amount of dust and CO2 in the atmosphere is already a given fact for Stuut. "In ice cores up to 800 thousand years old, drilled on Antarctica, you can clearly see that the amount of CO2 decreases when the amount of dust increases, and vice versa. I see it as our task to understand that relationship in much more detail."

Blanket and reflector

In addition to being a driver of algal growth and, thus, an indirect CO2 binder, dust also has a direct effect on the warming of our atmosphere, Stuut explains. "The smallest dust particles, flying high in the atmosphere act as a reflector on sunlight. They keep the solar energy away from Earth’s surface. At the same time, larger dust particles lower in the atmosphere are a kind of insulating blanket, that actually retains the heat that comes from the Earth's surface. If you want to know exactly how this distribution of large and small dust particles adds up, you will have to understand how the wind gets a grip on the grains."

Dunes as a model

To understand how the wind gets a grip on dust particles of different sizes, shapes and densities, Stuut no longer necessarily has to go to the ocean, he recently discovered. "We found out that the processes that take place above the Atlantic Ocean on the scale of hundreds or even thousands of kilometers, also take place in our own dunes, but then on the scale of tens or hundreds of meters. By looking at the shape and size of sand grains that are blown away in the dunes, we hope to eventually learn something about the transport of desert dust over much greater distances."

Wind from the past

When Stuut understands exactly what the wind is doing to large, small, round or flat grains of sand, he also hopes to be able to gain insight in the actual winds of the past, from deep soil samples from the ocean. "For builders of climate models, this is extremely useful information. We could learn from the past what the relationship between wind and climate has been. Extrapolating this to the future, it is important to know what the wind will do, as well as precipitation. Will the changing climate give us more deserts with more dust blowing around? Will more precipitation actually make the deserts greener? Will there be more or less sand blowing into the oceans? These are all questions in which desert dust plays a key role."

Oratie Jan-Berend Stuut donderdag 21 oktober 2021 | "Woestijnstof speelt hoofdrol in ons klimaat"

“Het is een isolerende deken, een reflecterend zonnescherm en ook mest voor de oceanen, waarmee algen worden gevoed; rondwaaiend woestijnstof speelt een veel grotere rol in ons klimaat dan veel mensen zich realiseren.” Dat zegt NIOZ-onderzoeker professor Jan-Berend Stuut in zijn inaugurele rede, waarmee hij Donderdag 21 oktober 2021 zijn leerstoel Eolische sedimentologie aan de Vrije Universiteit officieel aanvaardt.

Stof bindt koolstof

De relatie tussen stof en klimaat loopt voor een belangrijk deel via de algen in afgelegen delen van de oceanen. “Midden op de oceaan krijgen algen hun verse voeding vooral via de lucht, dus via stofdeeltjes. Maar behalve die voeding uit de lucht, nemen ze ook CO2 uit het water op. Wanneer op die manier de hoeveelheid CO2 in het water daalt, neemt de oceaan uiteindelijk weer extra CO2 uit de atmosfeer op. Op die manier zorgt vruchtbaar stof, via de groei van algen, voor beperking van het broeikaseffect”, legt Stuut uit.

Stofboeien

Voor het onderzoek van de groep van Stuut drijven al sinds 2013 enkele zogeheten stofboeien tussen Afrika en Zuid-Amerika op de Atlantische Oceaan. Die vangen binnenkort niet alleen stof, maar ook regen. “De stofboei ‘Michelle’ is recent uit de vaart genomen, maar op de boeien ‘Carmen’ en ‘Laura’, allemaal vernoemd naar promovendi uit mijn groep, zullen we binnenkort geavanceerde regenmeters plaatsen. We denken namelijk dat regen essentieel is om stof te veranderen in mest voor de algen in de oceaan. De essentiële voedingsstoffen zoals ijzer, stikstof en fosfaat die aan de minuscule zandkorrels geplakt zitten, zijn op zichzelf niet direct beschikbaar voor algen. Pas als het een tijdje wordt ‘voorgeweekt’ in een zoete en vooral relatief zure regendruppel, verandert de chemische vorm in een voor algen bruikbare voedingsstof. Als je dus wilt weten hoe stof de oceanen bemest, de algengroei stimuleert en daarmee CO2 vastlegt, dan zal je ook moeten weten hoeveel stof er met of zonder regenbuien in de oceaan terechtkomt.”

Dát er een omgekeerde relatie is tussen de hoeveelheid stof en CO2 in de atmosfeer, dat is voor Stuut al geen vraag meer. “In ijskernen tot 800 duizend jaar oud, die op de Zuidpool zijn geboord, zie je duidelijk dat de hoeveelheid CO2 afneemt wanneer de hoeveelheid stof toeneemt, en andersom. Nu is het zaak om die relatie in veel meer detail te begrijpen.”

There are many more negative and positive climate-related effects but the main link to the ocean is the fact that marine life may profit from nutrients in dust. When plankton reproduces, it takes up CO2 from the atmosphere. Thus, dust could potentially act as an ocean fertilizer, sequestering a greenhouse gas!

Deken en reflector

Behalve als aanjager van de algengroei en daarmee een belangrijke CO2-binder, heeft stof ook een direct effect op de opwarming van onze atmosfeer, legt Stuut uit. “Fijn stof dat hoog in de atmosfeer zweeft, werkt als een soort reflector op het zonlicht. Het houdt dus warmte weg bij de aarde. Tegelijk zijn grotere stofdeeltjes lager in de atmosfeer ook een soort isolerende deken, die warmte van het aardoppervlak juist vasthoudt. Als je wilt weten hoe die verdeling van grote en kleine stofdeeltjes precies verloopt, zal je moeten begrijpen hoe de wind vat krijgt op de korrels.”

Duinen als model

Om te weten hoe de wind vat krijgt op stofdeeltjes van verschillende groottes, vormen en dichtheden, hoeft Stuut niet meer per sé de oceaan op, zo ontdekte hij recent. “We zijn erachter gekomen dat de processen die boven de Atlantische Oceaan spelen op de schaal van honderden of zelfs duizenden kilometers, in onze eigen duinen óók spelen, maar dan op een schaal van tientallen of honderden meters. Door naar de vorm en de grootte van weggeblazen zandkorrels in de duinen te kijken, hopen we uiteindelijk ook iets te kunnen leren over het transport van woestijnstof over veel grotere afstanden.”

Wind uit het verleden

Wanneer Stuut precies begrijpt wat de wind met grote, kleine, ronde of platte zandkorreltjes doet, hoopt hij ook in diepe bodemmonsters uit de oceaan af te kunnen aflezen hoe hard de wind in het verre verleden nou écht heeft gewaaid. “Voor de bouwers van klimaatmodellen is dat bijzonder nuttige informatie. We kunnen dan uit het verleden leren wat de relatie tussen wind en klimaat is geweest. Ook voor de toekomst is het belangrijk om te weten wat de wind gaat doen, net als de neerslag. Krijgen we door het veranderende klimaat meer woestijnen met meer rondwaaiend stof? Worden de woestijnen door meer neerslag juist groener? Waait er straks meer of minder Saharazand de oceanen in? Het zijn allemaal vragen waar woestijnstof een sleutelrol in speelt.”

Inaugural lecture:

Prof Jan-Berend Stuut Stof tot nadenken

Thursday 21 October 2021,15:45 hrs, Vrije University Amsterdam (Faculty Science). Watch here: Inaugural Lecture prof.dr. J.B. Stuut - YouTube

Aeolian sedimentology

For his new chair of Aeolian Sedimentology, Professor Stuut studies sediment moved by the wind. Aeolus was the guardian of the winds in Greek mythology. So, in geology, aeolian processes are ‘wind-driven processes’, such as dune formation or erosion. "In the science around sediments, wind also plays a big role. For example, earlier research by our group at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research showed that sand from the Sahara is blown much further across the Atlantic than many colleagues ever thought was possible. Relatively large grains of sand from Africa, almost half a millimeter in size, even end up half-way the Atlantic Ocean ", Stuut says.

Eolische sedimentologie

Op zijn nieuwe leerstoel ‘Eolische sedimentologie’ houdt hoogleraar Stuut zich bezig met sediment dat door de wind wordt verplaatst. Aeolus was in de Griekse mythologie de bewaker van de winden. In de geologie zijn eolische processen dus ‘windgedreven processen’, zoals duinvorming of erosie. “In de wetenschap rond sediment speelt die wind ook een grote rol. Uit eerder onderzoek van onze groep aan het Koninklijk Nederlands Instituut voor Onderzoek der Zee bleek bijvoorbeeld dat zand uit de Sahara veel verder over de Atlantische Oceaan wordt geblazen dan veel collega’s voor mogelijk hielden. Relatief grote zandkorrels uit Afrika, van bijna een halve millimeter groot, komen zelfs halverwege de oceaan terecht”, aldus Stuut.