Caribbean islands face loss of protection and biodiversity as seagrass loses terrain

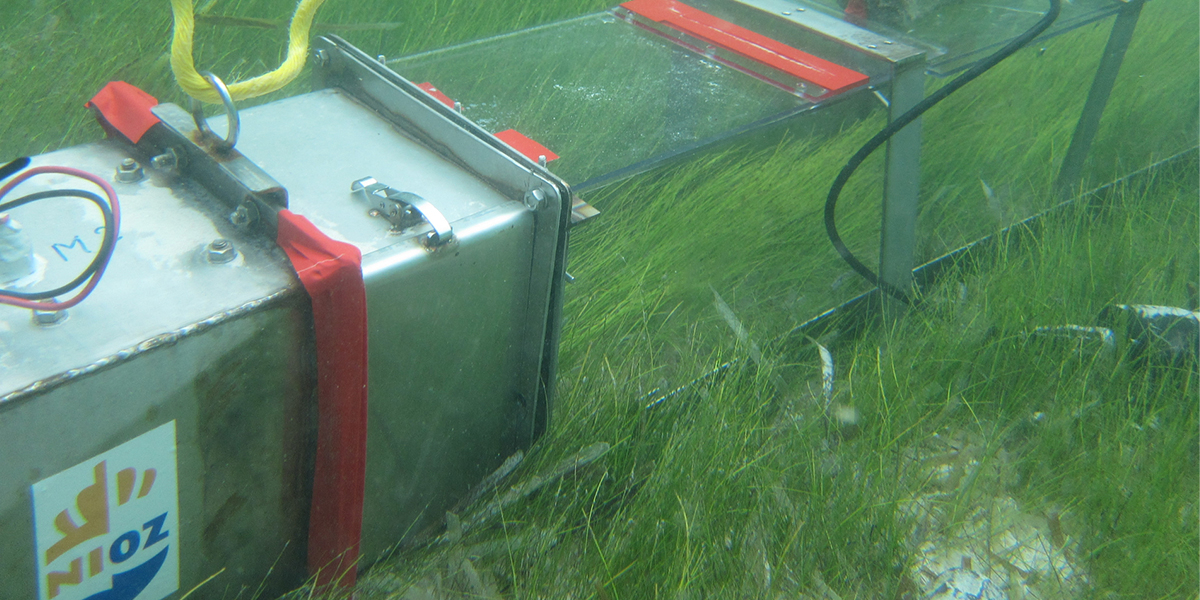

The flexible grass, that grows in shallow bays and lagoons throughout the Caribbean, is a natural wave dampener. As it sways back and forth, it removes energy from the waves, keeps the sand on the seafloor stable and, thereby, protects the beach against erosion. James: ‘It is a great natural protector of beaches and reduces the need for human intervention, such as sand nourishments and seawalls.’

Guardian of biodiversity

Seagrass offers more than protection to the islands and its people. The underwater meadows form a rich environment in which marine life, from micro-organisms to large animals, thrive. In turn, this benefits the local fishing communities. James: ‘In science, we call these ecosystem services.’ And seagrass serves many. James: ‘Through photosynthesis, seagrass removes CO2 from the water, it provides food and shelter for fish, turtles and sea urchins.’ Loss of these meadows not only puts tropical beaches at risk from erosion, it threatens all the species that rely upon them.

Scars that take years to recover

The biggest threats come from human disturbance, invasive species and bad water quality on the coasts. James: ‘Tourists flock to the Caribbean for the beautiful beaches and clear waters. Resorts, restaurants and bars have been built throughout the Caribbean to support tourism, however, often at the expense of the natural environment.’ Dunes had to make way for hotels, seagrass -and seaweed were removed to create perfectly groomed beaches, feet trample the meadows, and boat anchors leave scars; physical damage that takes years to recover.

A healthy seagrass ecosystem depends on healthy neighbours. And the grasses suffer under the damage done to nearby coral reefs or inland mangroves. James: ‘Coral reefs, mangroves and seagrass meadows are vital for a healthy Caribbean Bay. The systems are strongly connected and benefit each other.’ Animals move between the corals and seagrass meadows depending on their need for food or protection from predators or waves. Mangroves filter sediment that runs from the land into the ocean, improving water quality and clarity. James: ‘With more people comes more wastewater, which reduces the water quality when there isn’t sufficient water treatment.’ Over the years, more and more mangroves had to make way for farming and housing. With little left behind to capture the sediment, the water in the bays turns cloudy and dirty.

Restoring what was lost

As the pressure on seagrass increases from different directions, the importance of an integrated approach to protection, conservation and restoration becomes clear. James: ‘My more recent research shows that overgrazing by turtles and an invasive seagrass species (Halophila stipulacea) that is currently spreading around the Caribbean, reduce the coastal protection services. This example shows the importance to match conservation efforts of turtles with conservation of their habitats.’

To mitigate the negative effects of climate change and protect the biodiversity in our oceans, there is a great need for the natural self-sustaining strategies that seagrass meadows provide. However, James warns that in ecosystems it is not that simple to get back what was once lost. James: ‘Only 37% of seagrass restorations have survived. Projects like these take time, money and support from local communities and stakeholders. Working in coastal areas, waves and storms can undo hours of intensive restoration labour.’

James urges that we need to act fast to improve the health of seagrass ecosystems. ‘Only healthy ecosystems have a chance of withstanding the more extreme weather events, a rise in CO2, and rising temperature that come with climate. The rapid rate of this change gives us, and present-day ecosystems, little time to adapt to the new climatic conditions on earth. Yes, it will require substantial investments in resources and money, but the benefits will go far beyond coastal protection.’

Rebecca Kate James, The future of seagrass ecosystem services in a changing world (2020)

Defence

Fr 25-09-2020 at 12:45

Academy Building Online, University of Groningen

The defence can be attended online at:

https://www.rug.nl/digitalphd

Supervisors: Prof. T.J. Bouma, Prof. P.M.J. Herman (RU), Prof. T. van der Heide; Co-supervisor: Dr M.M. van Katwijk (RU)