Blog on gull research | Fish and chicks

We investigate what affects reproduction, and how this translates into changes in population numbers. The gull’s foraging areas in the North Sea are changing rapidly: large structures such as windfarms are built, fishing policies change, and sea water temperatures increase, which all may affect feeding opportunities for gulls directly or indirectly. Will this affect chick growth and survival?

We investigate gull’s diets by identifying prey remains. We find prey remains at their nest site, and, occasionally, a chick throws up its last meal when we measure it. These prey remains give us information on what chicks eat, but also where adults forage. The majority of the food chicks get from their parents has a marine or intertidal source.

Because diet is investigated since 2006, we notice shifts in what gulls feed their chicks. For instance, herring has increased and horse mackerel decreased as food source over the years. We also analyse the composition of stable isotopes in the blood of the chicks, which will tell us whether their food originates from land or sea.

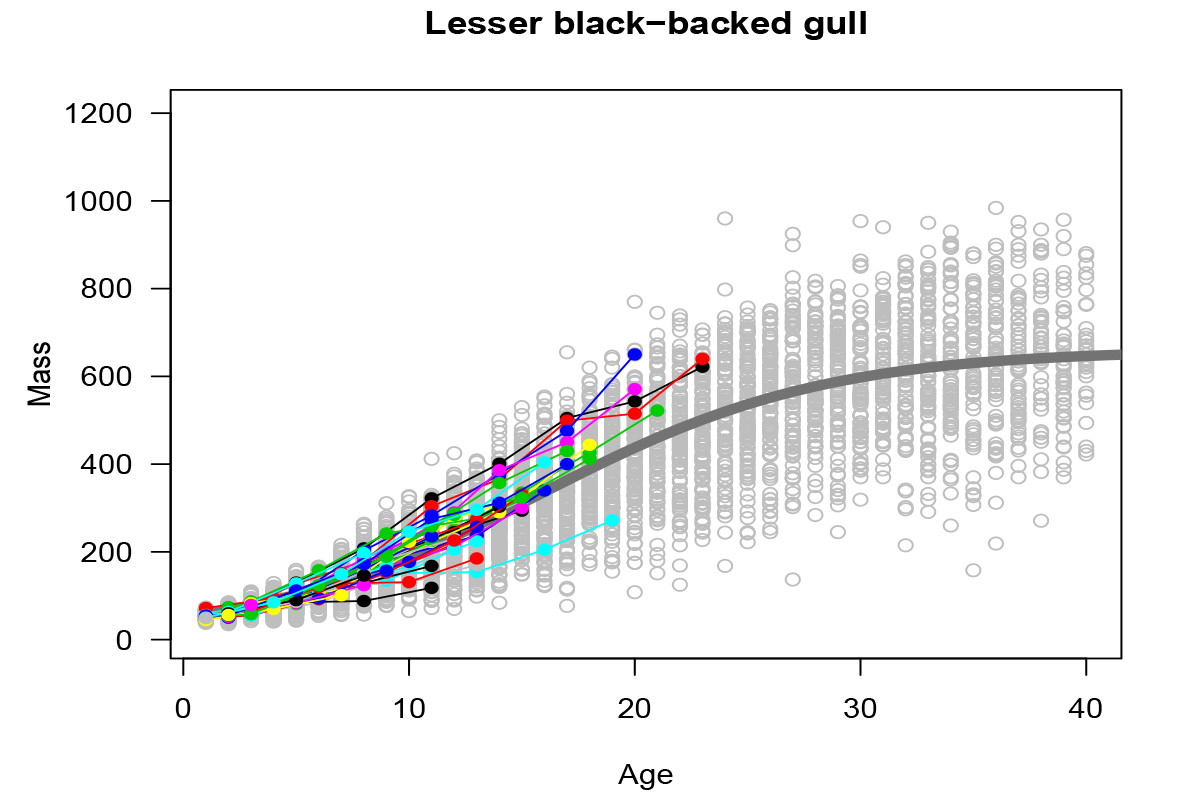

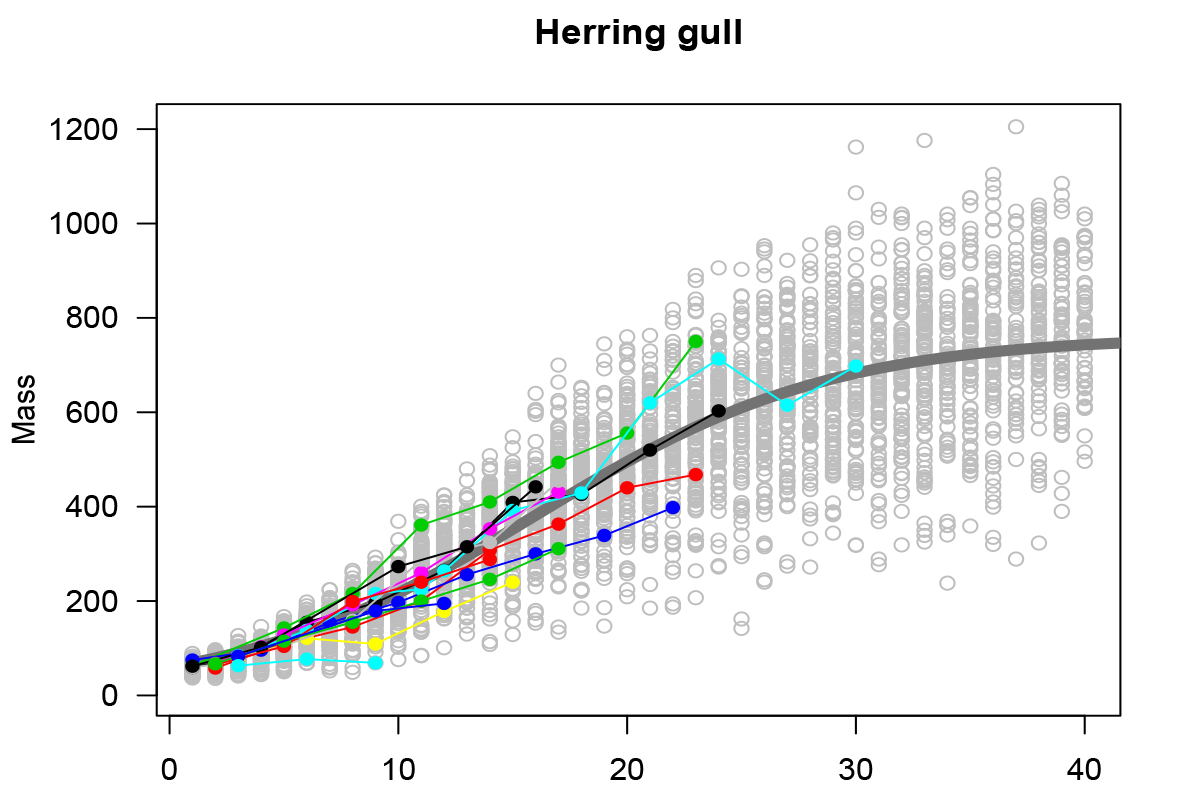

So far, this year Lesser Black-backed Gull chicks seem to grow well compared to other years (see graph). Most chicks are heavier then the average chick of their age. Although many Herring Gull chicks got predated just after hatching, those that survived show an average growth compared to previous years. Hopefully they can keep up in the coming weeks before they fledge! We will continue to measure the chicks every three days and hope many of them fledge healthy and heavy.

Figures above: Growth of Lesser Black-Backed Gulls and Herring Gulls. Grey points are all chicks measured 2006-2019, grey line is the average growth. Coloured points are those measured in 2020; each chick is connected with a line.