Acidification of seawater by absorption of CO2

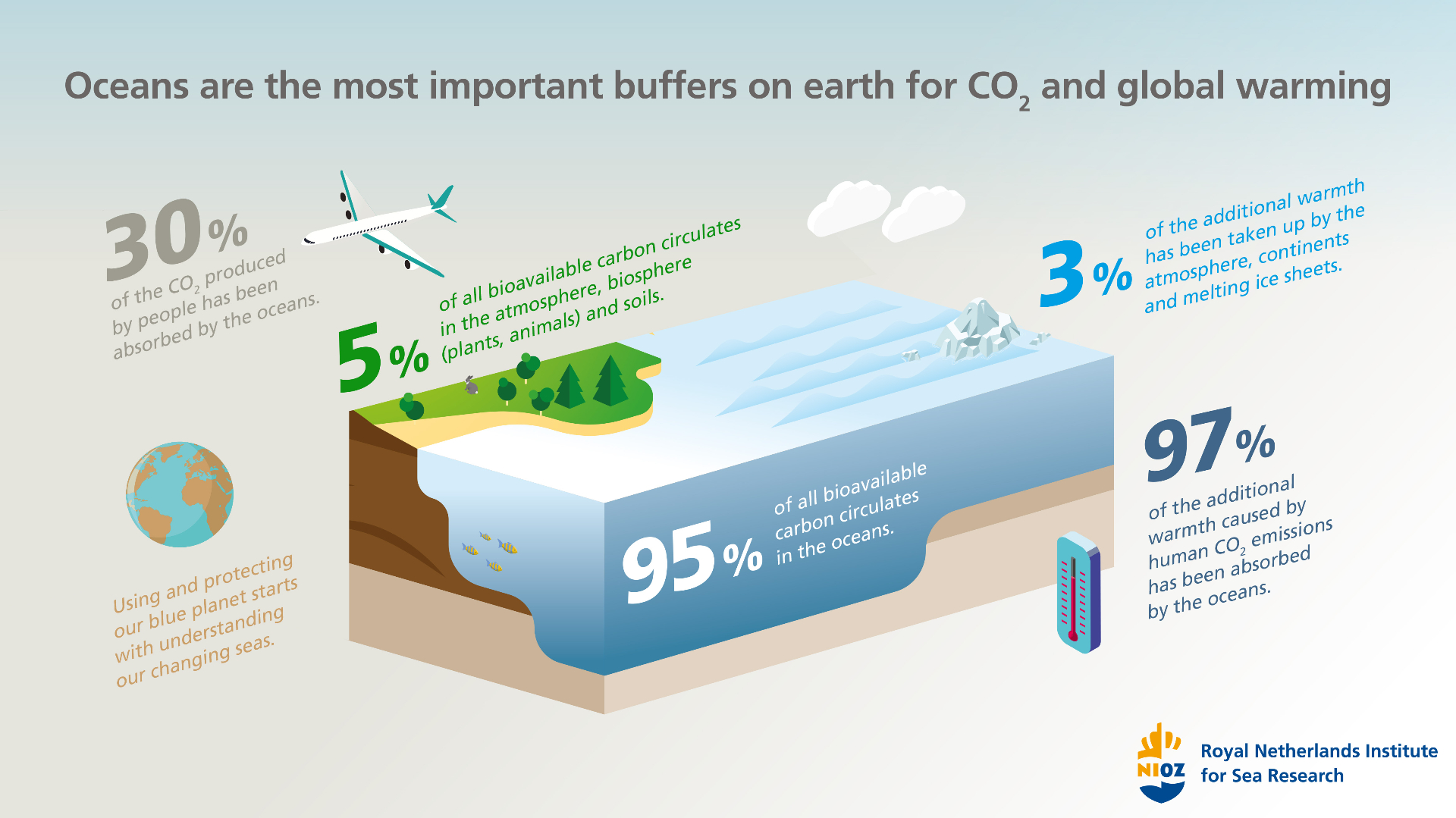

Acidification of seawater is caused by the enormous amounts of extra CO2 that humans bring into the atmosphere through the burning of fossil fuels. Almost a third of it is absorbed by the oceans. And that affects the composition of seawater. The concentrations of bicarbonate (HCO3-) and hydrogen ions (H+) increase. The latter causes an increase in acidity - the pH drops. However, the concentration of carbonate (CO32-) in seawater is decreasing. All kinds of organisms need carbonate for the development of their calcium skeletons.

Snail shells and mussels are made of the mineral aragonite. And aragonite dissolves more easily when acidified. So it becomes increasingly difficult for these animals to make and maintain their shells. But there are also organisms that make more calcium in an acidic environment. So it is not a simple black and white issue.

Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, the average pH of the upper ocean water has decreased from 8.2 to 8.1. That sounds like very little, but it is on a logarithmic scale. For marine life, it means a big change. Scientists see acidification penetrating at ever greater depths.

Verzuring van het zeewater door opname van CO2

Verzuring van het zeewater wordt veroorzaakt door de enorme hoeveelheden extra CO2 die de mens in de atmosfeer brengt, via de verbranding van fossiele brandstoffen,. Bijna een derde ervan wordt opgenomen door de oceanen. En dat beïnvloedt de samenstelling van het zeewater. De concentratie bicarbonaat (HCO3-) en waterstof-ionen (H+) neemt toe. Die laatste zorgt voor een stijgende zuurgraad - de pH daalt. Maar de concentratie carbonaat (CO32- ) in het zeewater neemt juist af. Terwijl allerlei organismen dat nodig hebben voor de aanleg van hun kalkskelet.

Slakkenhuisjes en mosselen zijn gemaakt van het mineraal aragoniet. En aragoniet lost bij verzuring makkelijker op. Het wordt voor deze dieren dus steeds moeilijker om hun schelpen te maken en te onderhouden. Maar er zijn ook organismen die in een verzurende omgeving juist méér kalk gaan maken. Het is dus geen zwart-witbeeld.

Sinds het begin van de negentiende eeuw is de gemiddelde pH van het bovenste oceaanwater gedaald van 8,2 naar 8,1. Dat klinkt als weinig, maar het is een logaritmische schaal. Voor het zeeleven betekent het een grote verandering. Wetenschappers zien de verzuring op steeds grotere diepte doordringen.

Key Figures

|

Kengetallen

-

Oceanen nemen 30% op van alle CO2 die door mensen wordt geproduceerd.

-

Van alle koolstof die op elk moment beschikbaar is voor biologische processen circuleert 95% in de oceanen.

-

De andere 5% zit in de lucht, bodem, in planten en in dieren.

-

Sinds het begin van de negentiende eeuw is de gemiddelde pH van het bovenste oceaanwater (tot 200 meter diepte) gedaald van 8,2 naar 8,1. (IPCC 2022) en de zuurgraad dus gestegen.