Sunlight pulps the plastic soup

UV light from the sun slowly breaks down plastics on the ocean’s surfaces. Floating microplastic is broken down into ever smaller, invisible nanoplastic particles that spread across the entire water column, but also to compounds that can then be completely broken down by bacteria. This is shown by experiments in the laboratory of the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, NIOZ, on Texel. In the latest issue of Marine Pollution Bulletin, PhD student Annalisa Delre and colleagues calculate that about two percent of visibly floating plastic may disappear from the ocean surface in this way each year. "This may seem small, but year after year, this adds up. Our data show that sunlight could thus have degraded a substantial amount of all the floating plastic that has been littered into the oceans since the 1950s," says Delre.

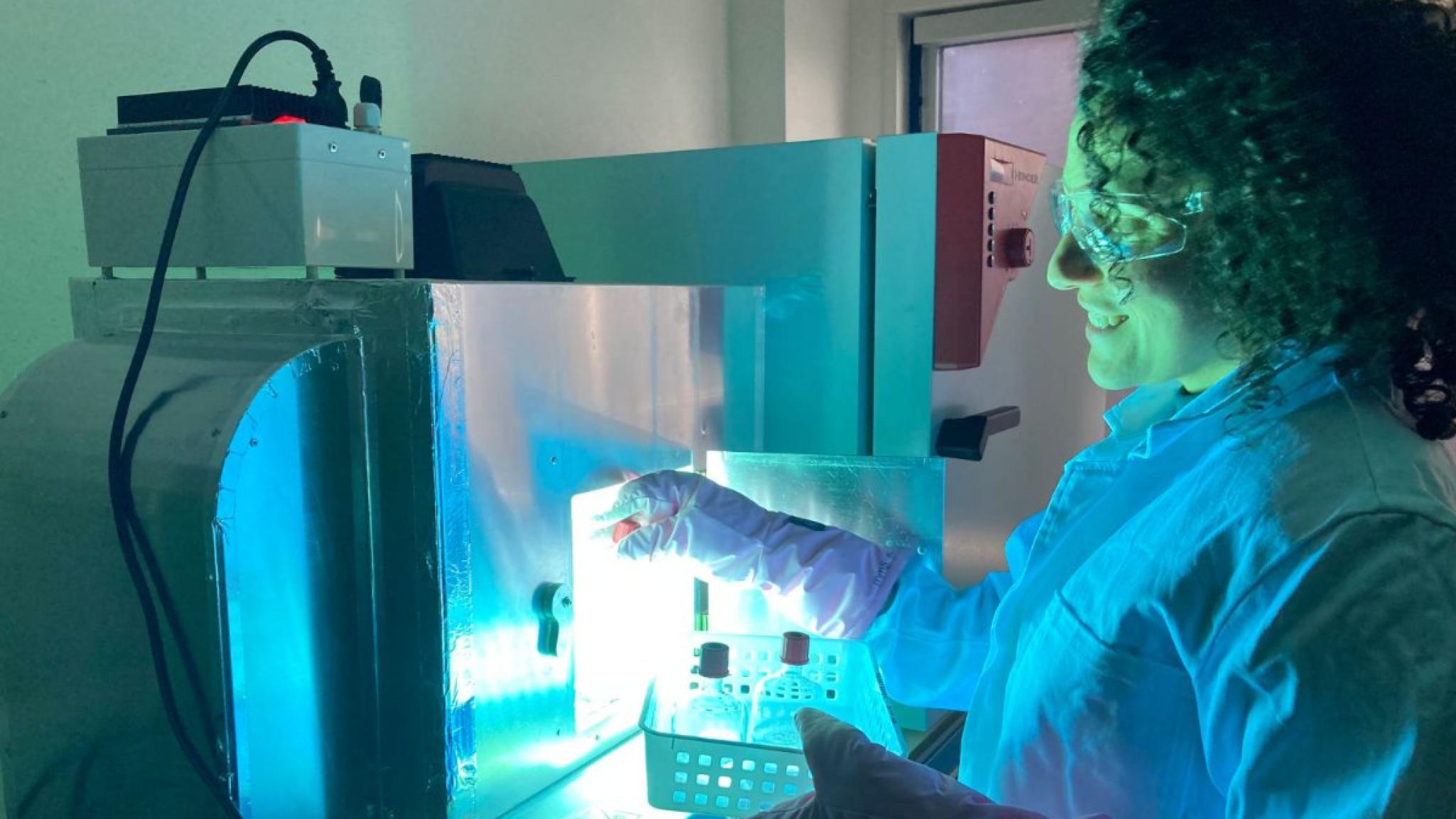

Annalisa Delre doing experiments with UV light in the NIOZ lab (photo: NIOZ)

Missing Plastic Paradox

Since the mass production of plastics began in the 1950s, a significant portion of plastic waste has made its way to the ocean via rivers, blown off from land by winds or directly dumped from ships. But the amount of plastic that is actually found in the ocean is only a fraction of what has entered the ocean. The majority is literally lost. In science, this problem is known as the Missing Plastic Paradox. To investigate if degradation by UV light can explain some of the vanished plastic, Delre and colleagues conducted experiments in the laboratory.

Artificial sun and sea

In a container filled with simulated seawater, the researchers mixed small plastic pieces. They then stirred this plastic soup automatically under a lamp that mimiced UV light from the sun. Gases and dissolved compounds including nanoplastics that leached from the degrading plastic pieces were then captured and analysed.

Slow degradation

From these measurements, the researchers measured that at least 1.7 percent of (visible) microplastics break down annually. For the most part it breaks down into ever smaller pieces including the (invisible) nanoplastics as well as into molecules that one also finds in crude oil. Potentially, some of these can be broken down further by bacteria. Only a small fraction is fully oxidized to the relatively harmless CO2.

Fed into a more complex calculation, accounting for the release of floating plastic to the ocean, beaching and ongoing photodegradation at the ocean surface, the breakdown by sunlight could have transformed a fifth (22%) of all floating plastic that has ever been released to the ocean, mostly to smaller, dissolved particles and compounds.

"With these calculations, we put an important piece in the jigsaw of the Missing Plastic Paradox in place," says Helge Niemann, researcher at NIOZ and professor of microbial and isotopic biogeochemistry at the Earth Sciences Department of at Utrecht University and one of the supervisors of PhD student Delre.

Effects on marine life

Potentially, there may be good news in this research, says Niemann. "In part, the plastic breaks down into substances that can be completely broken down by bacteria. But for another part, the plastic remains in the water as invisible nanoparticles."

In an earlier study with ‘real’ Wadden Sea water and North Sea water Niemann and colleagues already showed that a substantial part of the missing plastics floats in the oceans as invisible nanoparticles. "The precise effects of these particles on algae, fish and other life in the oceans are still largely unclear," says Niemann. "With these experiments under UV light, we can explain another part of the plastic paradox. We need to continue investigating the fate of the remaining plastic. Also, we need to investigate what all this micro and nano plastic does to marine life. Even more important”, Niemann stresses, “is to stop plastic littering all together, as this thickens the ocean’s plastic soup."

Microplastics of ~2 mm (photo: NIOZ)