Ice bubbles still hold methane in Arctic sediment during cold season

~~~ for dutch scroll down ~~~

Sediments of the Arctic Ocean hold a lot of methane, rising up from the deep ground. Above a water depth of around 400 meters, small amounts of this gas escape and dissolve into the sea water due to a natural process. In deeper parts of the ocean around Svalbard, gas often remains in sediments.

Gas hydrates enclose methane

Prof. Helge Niemann, biogeochemist at the NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute of Sea Research and Utrecht University (UU) explains how it works: “Due to the high pressure and low water temperature, in deeper parts of the water, so-called gas hydrates are formed: skeletons of water molecules that enclose a methane molecule. It looks like ice, and you can burn it”

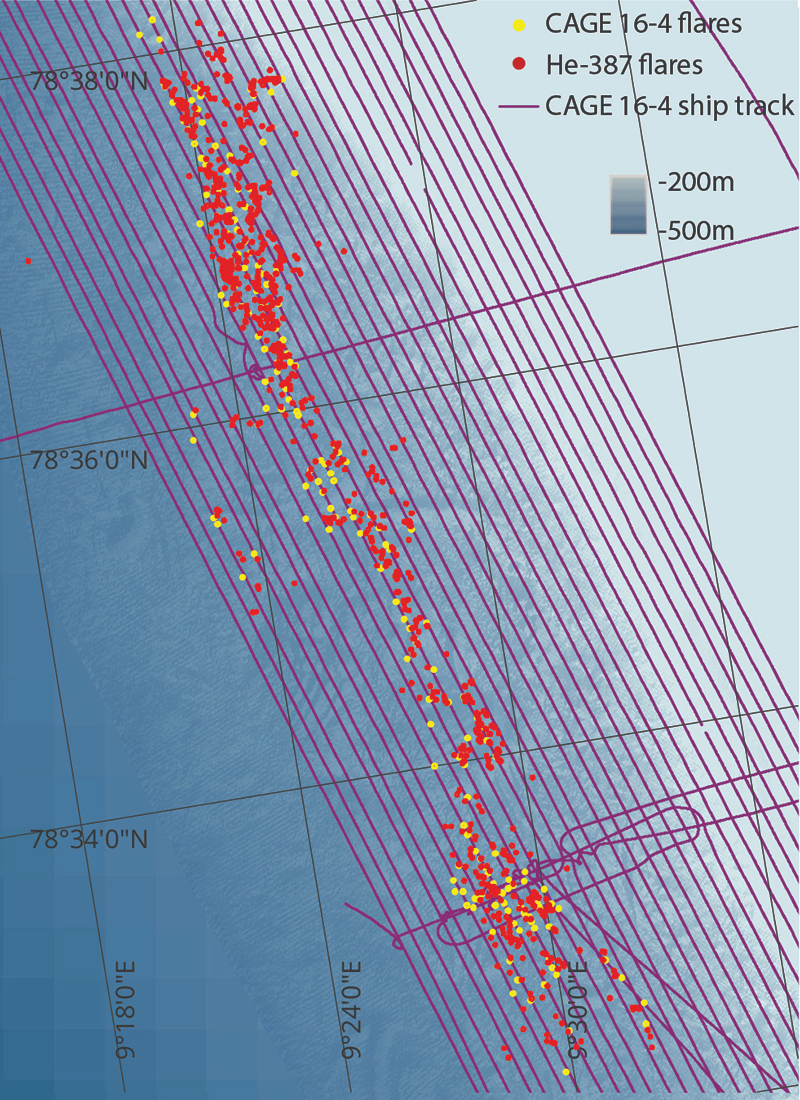

Niemann and his colleague Bénédicte Ferré, from Tromsø University in Norway discovered that in Spring, the boundary between gas leakage and gas storage is much farther away from the coast than during the rest of the year. “When, in Spring, the water is very cold, gas hydrates are stable up to a 360 meters water depth. But later in the year, the temperature of bottom water rises a few degrees, making gas hydrates disintegrate to a water depth of 410 meters and methane escape in gas bubbles to the water column.”

Disturbance of methane balance during 21st century

The researchers expect that ocean water warming will lead to disintegration of gas hydrates that are currently stable in the cold season. Niemann: “In the Arctic area, we expect a temperature rise of 3 to 13 degrees Celsius until the year 2100, compared to the temperature before the Industrial Age. The boundary of stable gas hydrates during Spring will move to deeper parts of the ocean, and that might put a stop to the seasonal differences of dissolved methane in the ocean water above the continental shelf.”

Niemann predicts the consequences: “With a higher influx of methane from the sediments, micro-organisms could become unable to break down all of the gas, disturbing the methane balance in the ocean. Rising through the water, methane could end up in the atmosphere and contribute to the greenhouse effect. As methane is a much stronger greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, it will have a higer impact on our climate.”

Enormous seasonal differences

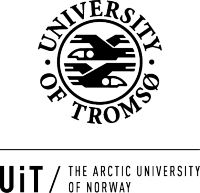

The publication in Nature Geoscience shows how much more methane is trapped in the ocean sediment during Spring, when the Arctic bottom water is at its coldest. In May 2016, an international team of scientists investigated a methane leaking seep on the continental shelf of Svalbard.

Niemann: “Normally, you don’t want to sail to the Arctic area in that time of year. Even after the ice has melted, the weather is horrible there, with great storms. It’s not nice to work there then.”

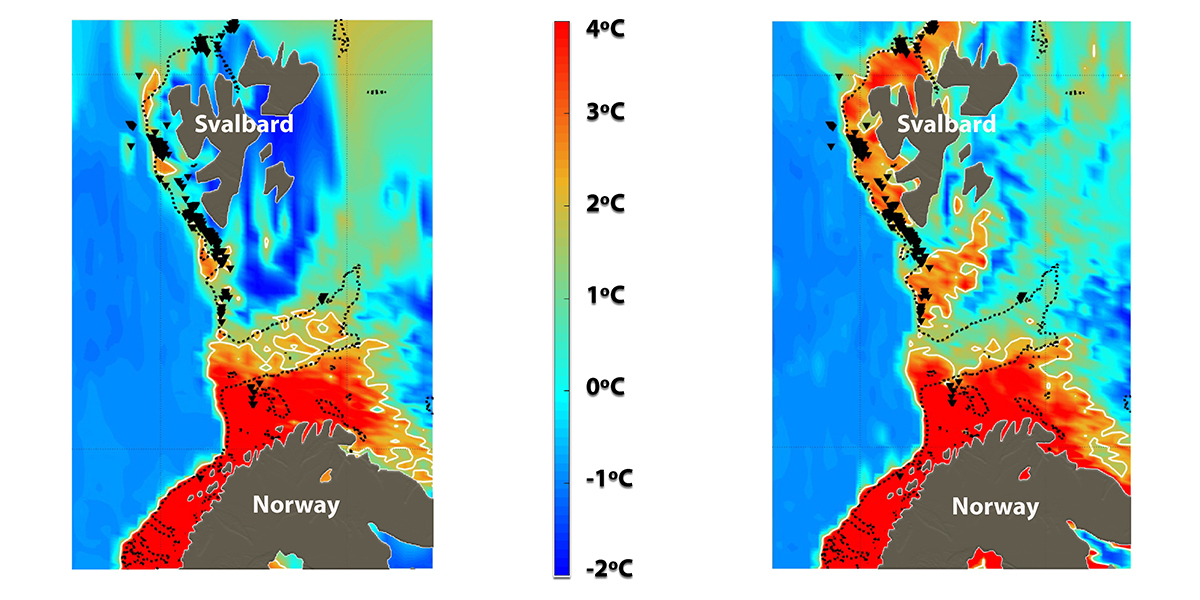

For their measurements, they used an advanced type of sonar. “With that, you can see the bubbles in 3D and calculate their volumes”, Niemann says. “We discovered that in the cold season, the sea floor emits almost 50% less methane than in the warm period. So, currently, there really is an enormous difference between seasons. Climate consequences until now are based on higher numbers of methane emission. By the time these numbers are met, the consequences might therefore also be larger.”

Publication

Bénédicte Ferré, Pär G. Jansson, Manuel Moser, Pavel Serov, Alexey Portnov, Carolyn Graves, Giuliana Panieri, Friederike Gründger, Christian Berndt, Moritz F. Lehmann, and Helge Niemann.

Reduced methane seepage from Arctic sediments during cold bottom water conditions.

Nature Geoscience. DOI:10.1038/s41561-019-0515-3

IJsbellen houden in koud seizoen methaan nog vast in Arctische bodem

Een deel van het jaar is de natuurlijke uitstoot van het broeikasgas methaan uit de zeebodem rond Spitsbergen maar de helft van wat tot nu toe werd gedacht. Opwarming van zeewater in deze eeuw kan dit seizoensgebonden verschil opheffen. Dat schrijft Helge Niemann van het NIOZ en de UU samen met een internationale groep wetenschappers op 13 januari 2020 in Nature Geoscience.

In de bodem van de Noordelijke IJszee zit veel methaan, dat omhoogkomt vanuit de diepe ondergrond. Bij een waterdiepte van ongeveer 400 meter ontsnappen, door een natuurlijk proces, constant kleine hoeveelheden van dat krachtige broeikasgas (ook wel bekend als moerasgas) en lossen op in zeewater. In diepere delen van de oceaan rond Spitsbergen blijft het gas meestal in de zeebodem zitten.

Gashydraten sluiten methaan in

Prof. Helge Niemann, biogeochemicus bij het Koninklijk Nederlands Instituut voor Onderzoek der Zee (NIOZ) en de Universiteit Utrecht (UU) licht toe hoe dat kan: “Door de hoge druk en lage watertemperatuur ontstaan in de diepere delen zogenoemde gashydraten: skeletten van watermoleculen die een methaanmolecuul omsluiten. Het ziet eruit als ijs maar is brandbaar.”

Samen met zijn collega Bénédicte Ferré van de Universiteit van Tromso in Noorwegen ontdekte Niemann dat die grens tussen het wel en niet lekken van methaan in de lente veel verder weg van de kust ligt dan in de rest van het jaar. “Wanneer in de lente het water heel koud is, zijn die gashydraten stabiel tot 360 meter waterdiepte. Maar later in het seizoen wordt het bodemwater een paar graden warmer, waardoor de gashydraten tot 410 meter waterdiepte desintegreren en het methaan via gasbellen ontsnapt.”

Verstoring methaanbalans in 21e eeuw

De onderzoekers verwachten dat de opwarming van het zeewater leidt tot het smelten van de gashydraten die nu in het koude seizoen stabiel zijn. Niemann: “In het Arctische gebied verwachten we tot het jaar 2100 een opwarming tussen de 3 en 13 graden Celsius ten opzichte van vóór het industriële tijdperk. De grens van stabiele gashydraten in de lente verschuift naar diepere delen van de oceaan en dat kan het seizoensgebonden verschil in hoeveelheid opgelost methaan in zeewater boven het continentale plat opheffen.”

Niemann schetst de verwachte gevolgen: “Bij een grotere instroom van methaan uit de bodem zullen micro-organismen misschien niet meer al het gas kunnen afbreken en de methaanbalans verstoord raken. Via het water zou methaan in de atmosfeer terecht kunnen komen en bijdragen aan het broeikaseffect. Methaan is ook nog eens een veel sterker broeikasgas dan kooldioxide, waardoor de impact op het klimaat ook groter zal zijn.”

Enorm verschil tussen seizoenen

De publicatie in Nature Geoscience maakt voor het eerst duidelijk hoeveel meer methaan in de lente, als door waterstromingen het Arctisch bodemwater het koudst is, in de bodem opgesloten blijft. In mei 2016 onderzocht een internationaal team van wetenschappers een methaanlek op het continentaal plat van Spitsbergen.

Niemann: “Normaal ga je met een schip in die tijd van het jaar liever niet naar het Arctisch gebied. Ook nadat het ijs gesmolten is, is het er nog vreselijk weer, met harde stormen. Het is echt niet leuk om er dan te werken.”

Voor hun metingen gebruikten ze een geavanceerde sonar. “Daarmee kun je de bellen in 3D zien en hun volume berekenen”, zegt Niemann. “We ontdekten dat in het koude jaargetijde bijna 50% minder methaan uit de bodem ontsnapt dan in de warme periode. Er is nu dus echt nog een enorm verschil tussen de seizoenen. De nu bestaande gevolgen voor het klimaat zijn gebaseerd op te hoge cijfers voor methaanuitstoot. Als in de toekomst die uitstoot wel gehaald wordt, kunnen ook de gevolgen dan ook groter zijn.”