Calciferous organisms are a good tool in climate research (but you should know how to operate it!)

~ For Dutch, scroll down ~

Acidity and temperature

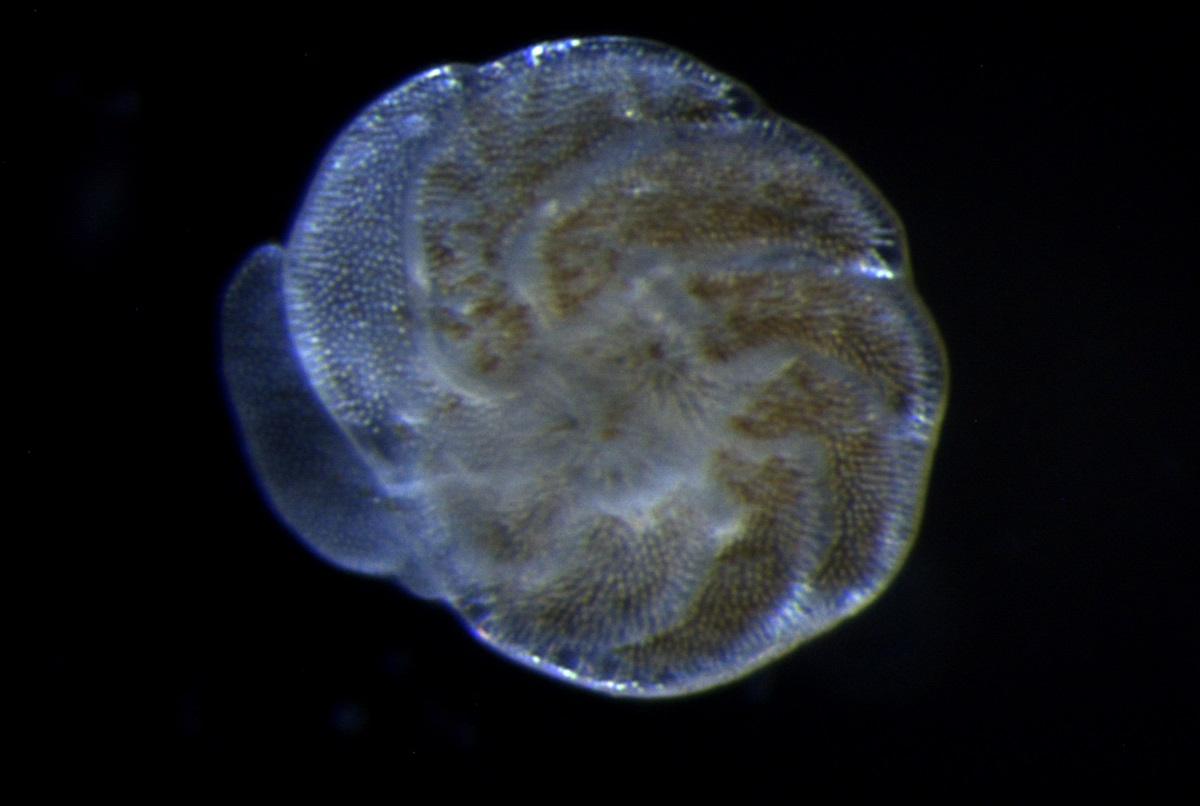

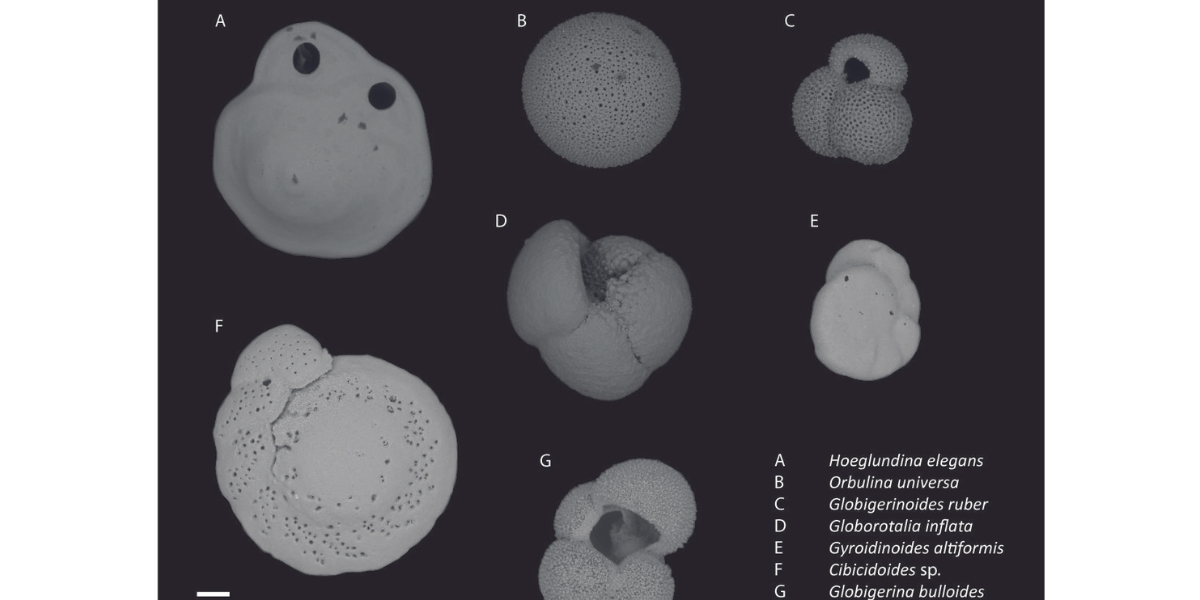

Foraminifers, or 'forams' for short, are single-celled organisms that make a tiny shell of calcium carbonate to protect their cell from the outside world. It is not unlike a house and even has ‘windows’ (foramina in Latin), hence the name. The shells consist not only of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) but also of traces of magnesium. "The amount of carbonate in the skeletons may reflect the amount of CO2 and the acidity of the ocean at that time," says Dämmer. "In addition, the amount of magnesium can tell a story about the temperature of the seawater. But that is not a simple black and white story," the researcher warns.

Light and dark

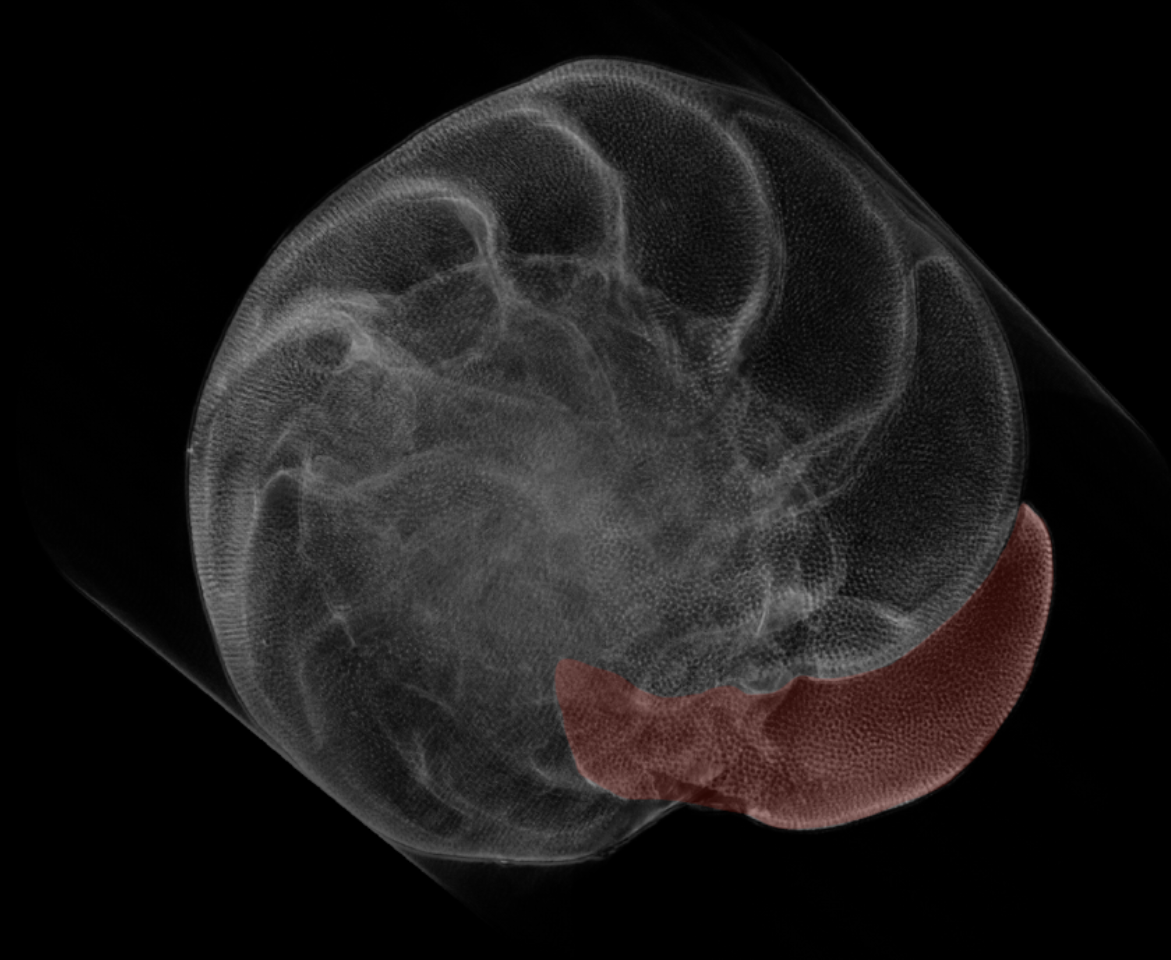

The amount of magnesium appears to be related not only to the temperature of the seawater, but also to the amount of daylight, Dämmer discovered during experimental culturing of her forams in the laboratory. If a specimen starts building a new chamber to add to its calcium skeleton at dusk, it will contain more magnesium relative to calcium than in a conspecific, calcifying in continuous daylight at the same temperature. "So, a simple translation of the amount of magnesium to the temperature in which that organism lived is a simplification of reality," Dämmer says.

More foraminifers with more CO2

Some species of foraminifers are likely to benefit from the increasing amount of CO2 in the oceans, that results from the anthropogenic emissions. That growth may well continue until the amount of CO2 in our atmosphere reaches 700 parts per million (in comparison: it is slightly over 400 ppm today). In addition, the acidity of the water will also become too high for these organisms to form calcium skeletons, meaning that even these resilient species will begin to struggle.

Chemical understanding

Dämmer is not primarily interested in the ecological consequences of an increase in one foraminifer or another. "In the food chains in the ocean you're probably not going to notice these changes. But to understand the complete accounting of CO2 and calcium in the oceans, it is very important to know exactly what these single-celled organisms are doing. In the open oceans, as much as half of the amount of calcium carbonate precipitated, consists of these tiny forams. In that respect, they can match coral reefs in other places in the oceans in terms of importance to ocean chemistry."

Prof. Dr. Gert-Jan Reichart (NIOZ/UU), Linda Dämmer's supervisor: "Linda's research is part of the NESSC, Netherlands Earth System Science Center, in which researchers from NIOZ, Utrecht University, Radboud University Nijmegen, Vrije Universiteit and Wageningen University & Research are investigating how warm the Earth is becoming as a result of climate change. Comparing seawater temperatures during past periods with high CO2 conditions plays an important role. At NIOZ, there is a lot of experience in growing foraminifers under controlled conditions. In this way, we improve reconstructions of seawater temperatures in the past and thus also improve seawater temperature predictions for the future.

Kalkskeletjes goed gereedschap voor klimaatonderzoekers

(maar je moet wel weten hoe ze werken!)

De fossiele kalkskeletjes van eencellige ééncellige foraminiferen zijn prachtige geschiedenisboeken, bijvoorbeeld om de CO2-gehalten in de oceanen uit het verre verleden mee te reconstrueren. “Maar om die geschiedenis écht te begrijpen, moet je eerst begrijpen hoe deze eencellige organismen hun skeletjes precies bouwen.” Die waarschuwing uit aardwetenschapper Linda Dämmer in het proefschrift waar zij vandaag op hoopt te promoveren aan de Universiteit Utrecht.

Zuurgraad en temperatuur

Foraminiferen, of kortweg ‘forams’, zijn eencelligen die een huisje van kalk maken, om hun ene cel te beschermen tegen de buitenwereld. Dat huisje heeft ook een soort ‘raampjes’ (foramina in het Latijn) wat de naam verklaart. De skeletjes bestaan niet alleen uit kalk (CaCO3) maar ook uit spoortjes magnesium. “De hoeveelheid kalk in de skeletjes kan iets zeggen over de hoeveelheid CO2 en de zuurgraad van de oceaan op dat moment”, zegt Dämmer. “Daarnaast kan de hoeveelheid magnesium iets zeggen over de temperatuur van het zeewater. Maar daar zitten wel de nodige haken en ogen aan”, waarschuwt de onderzoekster.

Licht en donker

De hoeveelheid magnesium blijkt niet alleen samen te hangen met de temperatuur van het zeewater, maar ook met de hoeveelheid daglicht, zo ontdekte Dämmer bij de experimentele kweek van haar forams in het laboratorium. Begint een eencellige bij het vallen van de avond met het uitbouwen van de kamer rond zijn kalkskelet, dan zit daar meer magnesium in ten opzichte van calcium, dan in een soortgenoot die bij dezelfde temperatuur, maar in continu daglicht leeft. “Een al te platte vertaling van de hoeveelheid magnesium naar de temperatuur waarin die eencellige heeft geleefd, is dus een versimpeling van de werkelijkheid”, aldus Dämmer.

Meer foraminiferen bij meer CO2

Sommige soorten foraminiferen zullen waarschijnlijk profiteren van de toenemende hoeveelheid CO2 in de oceanen, als gevolg van de uitstoot uit onze schoorstenen en uitlaten. Die groei kan misschien wel doorzetten tot een hoeveelheid CO2 in onze atmosfeer van 700 deeltjes per miljoen (ter vergelijking: nu is dat iets meer dan 400). Daarboven zal de zuurgraad van het water zelfs voor deze organismen te hoog worden om nog eenvoudig kalkskeletjes te kunnen vormen.

Chemisch begrip

Dämmer is niet zozeer geïnteresseerd in de ecologische gevolgen van een toename van de ene of de andere foraminifeer. “In de voedselketens in de oceaan ga je dit vermoedelijk niet merken. Maar om de complete boekhouding van CO2 en kalk in de oceanen te begrijpen, is het wel heel belangrijk om te weten wat deze eencellige organismen precies doen. Op sommige plekken in de open oceanen bestaat maar liefst de helft van de hoeveelheid vastgelegde kalk uit deze minuscule forams. Wat dat betreft kunnen ze zich qua belang voor de ocenaanchemie meten met koraalriffen op andere plekken in de oceanen.”

Prof. Dr. Gert-Jan Reichart (NIOZ/UU), promotor van Linda Dämmer: “Linda’s onderzoek maakt onderdeel uit van het NESSC, Netherlands Earth System Science Center, waarin onderzoekers van NIOZ, Universiteit Utrecht, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, Vrije Universiteit en Wageningen UR onderzoeken hoe warm de aarde wordt als gevolg van klimaatverandering. Het vergelijken van de zeewatertemperaturen tijdens periodes in het verleden met hoge CO2 condities speelt hierin een belangrijke rol. Het NIOZ heeft veel ervaring met het laten groeien van foraminiferen onder gecontroleerde omstandigheden. Zo verbeteren wij de reconstructies van zeewatertemperaturen in het verleden en daarmee verbeteren we ook de zeewatertemperatuurvoorspellingen voor de toekomst.

PhD defence: Elements and isotopes in foraminifera: Magnesium uptake, biomineralization and proxy application.

29 November 2023, 12:15-13:00

Utrecht University Hall, Domplein 29, and online via this link