~~~Where is our Dutch research vessel Pelagia? Track&Trace her whereabouts ~~~

Laura Villanueva and Rick Hennekam, cruise-leaders:

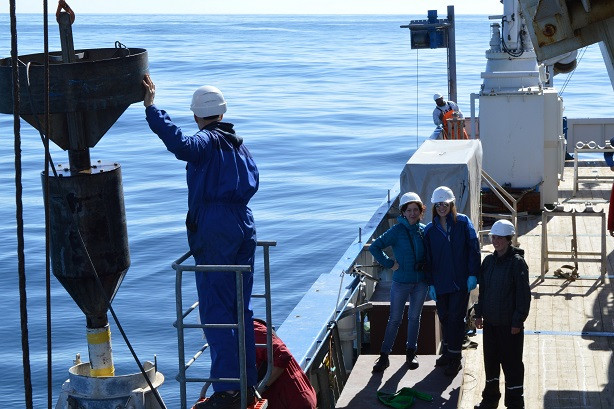

At the end of March, beginning of April 2017, we did a one-week cruise on NIOZ’ research vessel Pelagia to the Black Sea collecting the necessary samples and performing experiments on board in a joint effort of the NIOZ departments Marine Microbiology and Biogeochemistry (MMB) and Ocean Systems (OCS).

Oxygen is present only in a very shallow surface layer below which the water column is completely depleted of oxygen. Therefore, the water column shows multiple redox gradients. This is an ideal setting to determine the physiology and role of the different anaerobic microbial communities in current and past oxygen-depleted (anoxic) systems. Because of the nicely layered (‘laminated’) sediment on the deep-sea floor, the Black Sea is also very suitable for reconstruction of past climate variability.

Wrap-up blog:

After 9 days on board of the R/V Pelagia we finished our sampling campaign in the Black Sea. It’s been a great experience and we can’t ask for more! The weather was amazing, calm sea, beautiful sunny days and most importantly, we come back home with many samples to analyze both the microorganisms and also the laminated sediments in the mysterious and exciting Black Sea. For us, as scientists, having the opportunity to go outside of our daily life in the lab is priceless. We will use this inspiring experience to recharge our batteries and come up with new scientific questions to answer. We would like to thank the crew of the R/V Pelagia for their amazing support and to make possible all our crazy sampling wishes. Also we would like to thank you all out there to follow our blog and in social media. We will keep you posted of our upcoming projects and the outcome of the #BlackSea2017 campaign.

You can find the blogs below, ordered from last until first

Final Day 9: 04/04/2017 - Julie Lattaud

Hi everyone, today was the last day of cruise 64PE418, it has been an interesting day, a gorgeous set of multicore obtained and a bent piston core. It was my first cruise and it has been an amazing experience, first of all I didn’t get seasick (which make the whole experience more enjoyable) and then everything, from the friendly crew to the gorgeous weather and the passionate scientific staff, just great! And all this science, our staff on board was a mix of paleoclimatologists, geologists, microbiologists, geochemists, making the evening lectures diverse and the discussions interesting. My work at NIOZ is focused on developing a way of reconstructing past riverine input in the sea using special organic compounds, for that I collect water and sediments from rivers but also sediments from the ocean (I collected 4 surface sediments from the Black Sea, and they will be integrated to a wider study that focus on the Danube River and its input in the Black Sea). To summarize our cruise: 2.5 piston cores, 23 multicores, thousands of liters of water filtrated, several dolphins’ visits, one ankle, a lot of delicious food, that’s it! THE END.

Day 8; 03/04/2017 - Ibtissem Sabbar

Hi I am Ibtissem Sabbar and I am a Bachelor student Analytical Chemistry in Leiden. I am working for my Bachelor thesis at the NIOZ for 9 months, trying to improve measurement of trace elements (elements that can tell us something about oxygen deficit environments, such as the Black Sea) in sediments through different measuring techniques. This is my first scientific cruise, and so far it’s been very good. Rick Hennekam is my supervisor and together we will work on the sediment cores from the Black Sea.

Today was our first day at the fourth station. The day started very nice, it was sunny and the sea was calm. Today we mainly work on the microbial communities in the water column. However, I’ll be working mainly on sediment material taken with piston and multi corers. The multicore is a piece of equipment used to sample several sediment cores (of about 55 cm in our case) from the bottom of the Black Sea. We will analyze these cores in our lab at NIOZ, Texel, to say something about the trace element variability that relates to the history of oxygen deficiency in the Black Sea. Yesterday, we also took a long piston core, which we will use to go even further back in time. Rick was asking everyone on board to take a guess on how many meters of sediment the piston core sampled. The person that guesses the actual length wins a beautiful price (such as a drink at the bar, or a half-eaten Toblerone…yes, the supplies are limited on board of a ship). Also, the cutting of the core was something we could turn into a game. We had to cut the core into pieces of 1 meter, and Darci and Rick tried to beat each other in being the quickest. Darci won! This way, the whole process went very fast, which was great. We ended up obtaining 11.35 meter of sediment from the piston core.

The second day of core sampling yesterday was thus very successful, with the help of an amazing team of people! During cutting of the piston core we sailed to the next and last station of the Black Sea expedition at which we work today. I hope this station goes as well as the three previous ones!

Day 7; 02/04/2017 - Saara Suominen

Another day on the Black Sea has blessed us with sunshine, calm waters and dolphins. Today we have taken a piston core (11,3 m) and a successful multicore at a new station after which we have moved straight to our last station. I have had a day of reading and writing after a busy week of collecting as many samples as possible for analyses at the NIOZ.

I am on board the Pelagia to study the activity of micro-organisms, which are able to survive in the extreme conditions of no oxygen. Most of these organisms remain unknown to us, because they require very specific conditions to their growth that are difficult to replicate in the laboratory. Therefore I am trying to use more direct methods where the water is manipulated as little as possible to get a hint on how these lifeforms deal with the hostile conditions they are living in and how the communities work together to degrade organic matter in the water. Understanding how these organisms live is important for clarifying the functioning of essential anaerobic processes and global carbon cycles, and can also give us a hint on the origins of life and its peculiarities.

I have collected over 400 l of water, particulate organic matter from over 1600 l and dozens of liters of filtered water to determine the type of organic matter that is residing here. I have just finished an experiment where I fed the organisms special organic matter that can be traced back in the DNA of the cells that have used it for their growth. With this method we can directly observe which organisms are eating the type of food that we provide.

This is my second time on the black sea, and while I start to get more familiar with what is known of the processes going on in these waters I start to appreciate more and more what a unique environment we are able to work with. Life in the Black Sea can provide us with many insights on the diversity of life on this planet, and there remains much work to do.

Day 6; 01/04/2017 - Rick Hennekam

Today we moved on to the next station after four days of extensive work at the first site, which focused mainly on microbial communities in the water column. At our second station we focus on the sediment, and taking cores of the sediment, as these form a natural environmental archive of the Black Sea. The day started well, with dozens of dolphins surrounding the R/V Pelagia while we moved to the next site. After a slightly rougher day at sea yesterday (and hence no Blog update, sorry), everything is calm again and thus perfect for taking as long as possible sediment cores.

Sediments are a core business for the OCS (Ocean Systems) department of NIOZ, as we aim to investigate the oceans in the past and present to assess their future role. I (Rick Hennekam) specifically focus on so called restricted basins (seas with limited connection to the global oceans), such as the Mediterranean Sea, Red Sea, Baltic Sea, and Black Sea. These type of seas are vulnerable environments, because they are relatively small in size (compared to oceans), which makes their circulation patterns extremely sensitive to changes in climate. Circulation maintains oxygen transport to the deeper parts of restricted basins, and thus when the circulation is interrupted this can cause depletion of oxygen and inhibition of life at depth. The Black Sea, for instance, is completely depleted of oxygen (anoxic) below ~75 meters, making it the largest body of water on Earth that is anoxic at depth. For my project we will take cores from the Black Sea to reconstruct the development of anoxic conditions in the past. This data will be used in our models to better define the thresholds - often called tipping points - where restricted seas shift into a basin-wide anoxic state, providing important constraints for our future seas and oceans.

Obtaining the right samples is key, before we can do this science. We were happy today to obtain 9,83 meter of sediment in a long core and several shorter (~54 cm) sediment cores. The first day of coring was thus very successful and we hope we can keep this up for the next 3 days, as we will continue to collect more of these smelly sediments. I cannot wait for the material to arrive at the NIOZ Texel…only 3 weeks left!

Day 4; 30/03/2017 - Sigrid van Grisven

Hi! This is Sigrid. As promised by Laura in her blog, I will tell something about what I do on board.

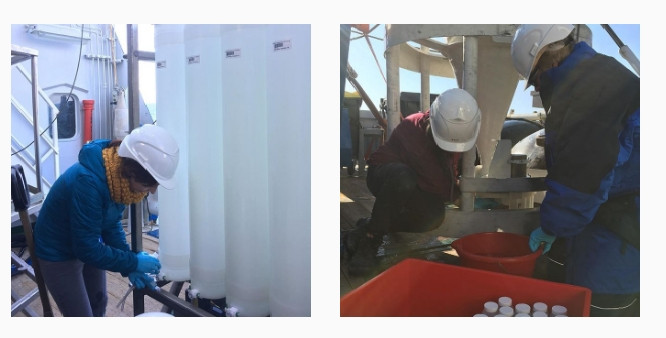

Whilst others enjoy the sun outside on the deck, I'm wearing a hat, scarf and many layers of clothing. My work is done in a temperature controlled container, which is at 7*C now. A bit chilly! But luckily I get a lot of help from the other people on board, so I don't have to spend too much time in there.

My container is at 7*C because that is the temperature of the deep water of the Black Sea. Inside incubations are going on in bottles. Those bottles contain water from 130m or 1500m depth, with some chemicals in it. Because there are alive microbes in those bottles, and I want them to stay alive and grow, I try to keep them nice and comfy at their normal temperature. It's already a big change for them to be at atmospheric pressure, instead of having the enormous pressure of 1500m water on top of them!

The reason I have this incubations is because I want to study how microbes in the Black Sea consume methane. Methane is a greenhouse gas, that is produced in the sediments and can travel all the way up to the surface water, and from there to the atmosphere. We don't want that, because methane is one of the causes of global warming. But luckily, there are these methane consumers that can use up part of the methane before it reaches the atmosphere. My research is focused on finding who those microbes exactly are, what things besides methane they like to use, and how much methane they can consume. And for such a nice research topic, I'm definitely willing to stand in a cold container!

Day 3; 29/03/2017 - Laura Villanueva

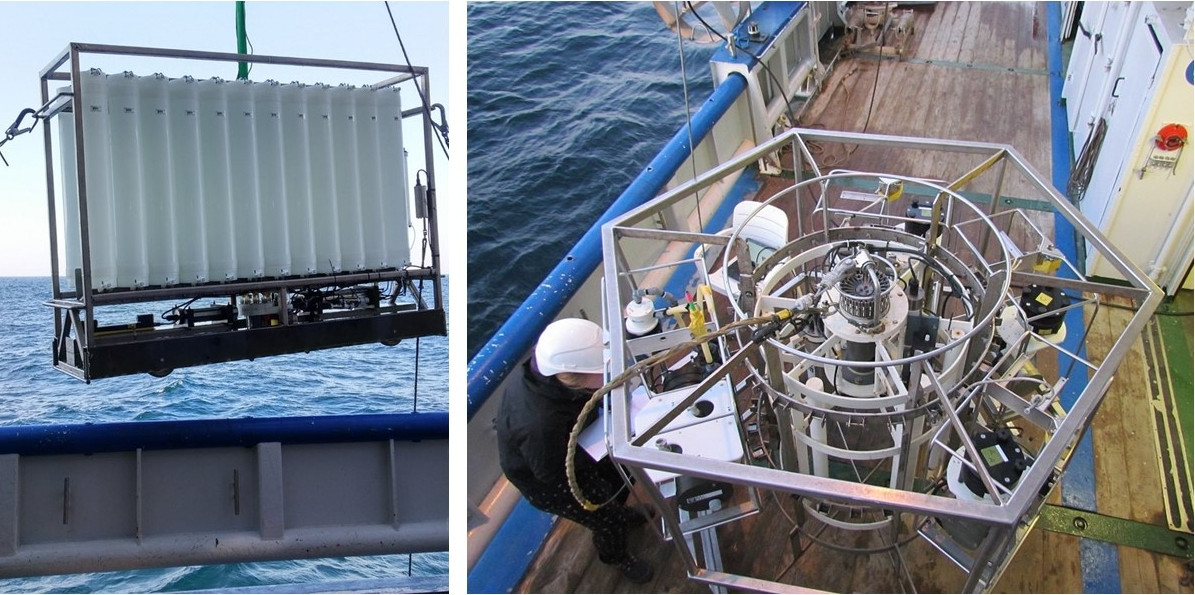

Today is our second working day in the Black Sea 2017 campaign. This morning we recovered the 4 in situ pumps that had been pumping suspended particulate matter all night. Marianne and Denise recovered the precious filters and the data recorded by the computer. Many liters filtered! A successful deployment! This means we will have enough material to analyze which microbes live at 2000 meters depth. Most importantly, we will also determine which membrane lipids do they make. Microbes have lipid membranes that surround them and protect them (like our skin!). Some of the lipids that form these membranes are unique for a given microbe which means that if we encounter these lipids in the environment or in very old sediments we can tell if those microbes were already there in past times.

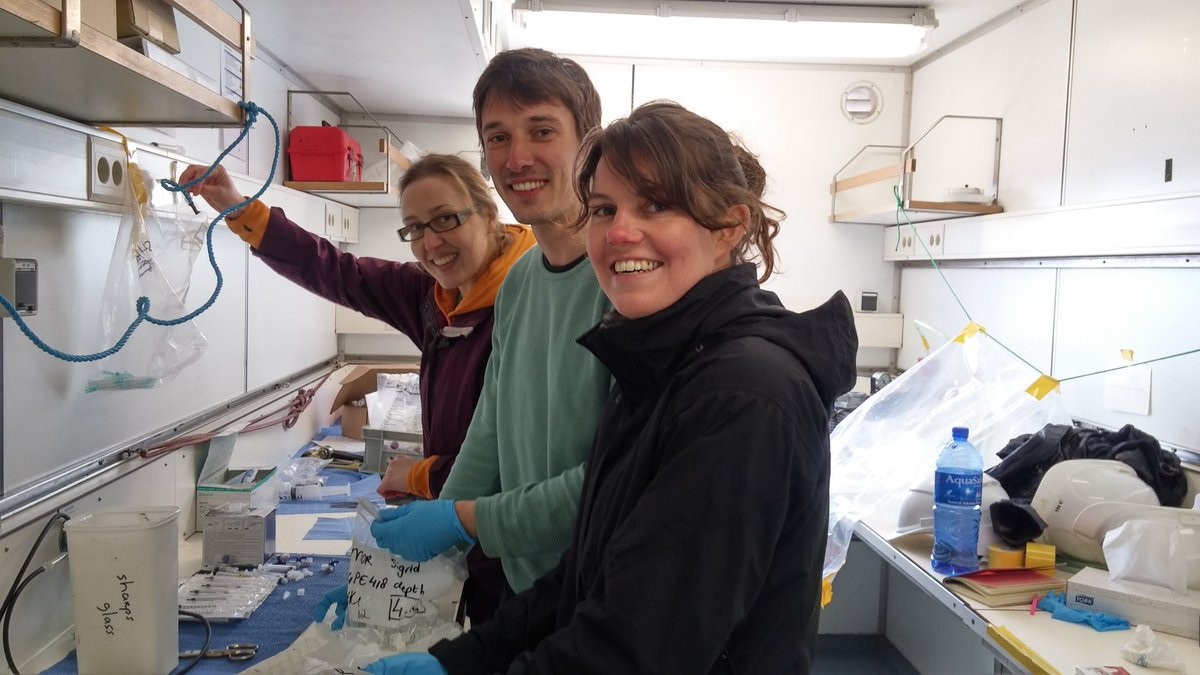

Then, we deployed the clean CTD to get water at different depths. Both Sigrid and Saara need this water for incubation experiments (they will tell you more in later entries!). The microbes we are looking for in the Black Sea don’t like oxygen, which means we have to keep the oxygen away if we want to keep the microbes happy. To do so, we need to attach a tube to the bottles to flush them with nitrogen. Then, we can attach a tube to CTD bottles that ends on a syringe needle and with it we puncture glass collection bottles that are already free of oxygen. We had to fill up many bottles of water for the experiments so we all helped out to get the work done as soon as possible. The water below 70 meter or so in the Black Sea has a high concentration of sulfide so that means that we also had to deal with the smell of rotten eggs during the sampling (which it was not so bad). Let’s hope that the sampling didn’t disturb the microbes so much and they can happily recover and be active during the incubation experiments planned. This afternoon and evening we will continue with more water pumping with the in situ pumps…but first some lunch and an ice cream to recharge our batteries, let’s go!

Day 2; 28/03/2017 - Nina Papadomanolaki and Christine Boschman (both Utrecht University)

Yesterday we departed from Port Varna. For us (Nina and Christine) this is the first time on sea so we are a bit nervous about getting sea sick. Luckily, the weather is really good, so the waves are not so high. And still, it feels really weird. Everything is moving constantly. The first day we feel like we are drunk, constantly trying to keep our balance. But you get used to it.

Yesterday we did some preparatory work. As this is Christine’s first cruise and even the first thing she does for her PhD, her job is mainly to learn and gain experience. Which means that, the first couple of days, she’s mainly standing in the sun and watching how other people do the work. It’s all really interesting to see, so she’s not complaining. Nina is, however, already very busy this day, so she’s walking around with mud everywhere on her clothes, it looks nice.

This morning, we picked up Nina’s sediment trap from Utrecht University that has been here since 2015, collecting sinking ‘mud’ out of the water column for a year. We had to look for a yellow or orange buoy which would float around somewhere here. It was hard to find, and when we saw it, we knew why. It wasn’t orange anymore, it had turned dark brown. Maybe that’s why this is called the Black Sea. Beneath the buoy, four sediment traps were situated at different depths. The deepest trap was hanging at about 1800m. Once the traps were on the ship, the bottles that were hanging under them could be taken off and shut. Some were full with mud and smelled like rotten eggs, others were mostly empty. So the traps had done their job well, collecting ‘mud’, sediment, that scientists could work with back in Utrecht.

This afternoon we lowered the CTD towards 2100m depth, which is an instrument that measures properties of the water at different depth. It’s basically a collection of bottles, each of which fills with water at a different depth. The water can then be analyzed in the lab or used for growing microorganisms. Lowering the CTD to the bottom of the sea takes a while, which gives scientists and members of the crew time to talk while sitting in the sun. We like this kind of research.

Day 1; 27/03/2017 - Darci Rush

Today, 27-03-2017, is the day the ship sails from Varna, Bulgaria to embark on our Black Sea research cruise. For the next 10 days, we will be sampling the water column and sediments, searching for exciting life and records of past climate in the area. The majority of the first days of our work on board will be to see what is happening in Black Sea water below 70-80 meters. Below this water depth, oxygen is depleted, or anoxic. Substances that are usually considered toxic accumulate under anoxic conditions, and common marine life (plankton, fish, dolphins, etc.) cannot survive. However, organisms that use alternative molecules to oxygen are thriving. Which is why we are here.

Laura Villanueva, Sigrid van Grinsven, and Saara Suominen, are members of Soenghen Institute for Anaerobic Microbiology (SIAM). They will be collecting water and particulate material to investigate which redox reactions are taking place in anoxic Black Sea water and which microscopic organisms (bacteria and archaea) are responsible for these pathways.

On board, I (Darci) will be looking more specifically at the methane that escapes these anoxic waters, and reaches the oxic waters above 70 meters. Here live bacteria that can “eat” methane, using oxygen, to produce carbon dioxide. I am interested in finding a way to trace how this process of “aerobic methane oxidation” has varied in the past. This is important because methane is a very potent greenhouse gas, and fluctuations in the release of atmospheric methane over long time scales has been proposed to significantly affect climate and cause warming events. As an organic geochemist, I use lipids as “biomarkers”. The bacteria that perform aerobic methane oxidation produce specific biomarkers that we can look for in marine sediments, records the climate of the past. We’ll hear more about these climate records from Rick Hennekam, who will be drilling sediments from the Black Sea later on in this cruise. From the biomarker information we extract from the sediment record, we can have a better estimate of how much methane was potentially being released into the atmosphere during past warming events.