August 6 - From Transit to Voyage...

Having made very good time so far, we decided to deviate a bit yesterday to explore the microplastics levels between some of the Aeolian Islands on our transit. We've been detecting much more visible macroplastic here near the coast (although not systematically keeping track of larger litter) and perhaps, not surprisingly, also found among the highest microplastics counts along our cruise track to date. After an amazing barbeque alongside the still active volcano on the island of Stromboli, we held our science-wrap up meeting after sunset with flash talks and data summaries by all participants. We've been calling this the "Microplastics Transit Cruise" because the RV Pelagia needed to get from the Azores to Sicily to prepare for her next cruises leaving from the Mediterranean, but with just 48 hours of wire time it has been much more than a transit: we are very pleased to report that the trip has far exceeded expectations with a total of 37 stations that included 22 Manta Trawls, 12 CTD hydrocasts and four box cores alongside continuous flow through measurements of plastic, phytoplankton and plastisphere community assembly incubations. We steamed through the Strait of Messina this morning en route to our port of Catania where our journey will end. What was intended to be a transit has blossomed into so much more, making the voyage all about the journey and not the destination in more ways than one.

August 5 - Plastics in sedimentary environments

We collected our final sediment sample this afternoon right after lunch and before our 500- meter CTD hydrocast. Although we will not have time to examine these sediments for the presence of microplastics onboard, they will be returned to the laboratory at NIOZ to examine them for this purpose and also to enrich for possible biodegrading bacteria.

Presently marine biodegradation standards are written for sandy sediment environments, but we know little about the behavior of biodegradable and compostable plastics in other types of aerobic sedimentary environments or even anaerobic (oxygen-free) ones. Deeper ocean waters and the bottom of the ocean are typically dark and cold - so it is important to understand what happens to plastic when it sinks down into the water column because of organisms that grow on it or because it is made out of the kind of plastic resin that is denser than seawater and thus sinks. In the Mediterranean we have sighted several pieces of floating macrodebris just by looking from the deck, but also detected tiny fibers using a microscope.

Linda Amaral-Zettler

August 4 - Pelagia, Plankton, and Plastic!

Plankton are a diverse group of small aquatic organisms that drift wherever the water takes them, forming the base of the food web in most marine systems and serving as food for larger animals including the filter-feeding baleen whales.

Many plankton can swim but not strongly enough to move against currents in the water. Members of the plankton range in size from microscopic single-celled algae that we can only detect with our flow cytometer (see July 31st blog entry) to animals like crab larvae, "krill", and floating jellies such as Porpita porpita known as "Blue buttons".

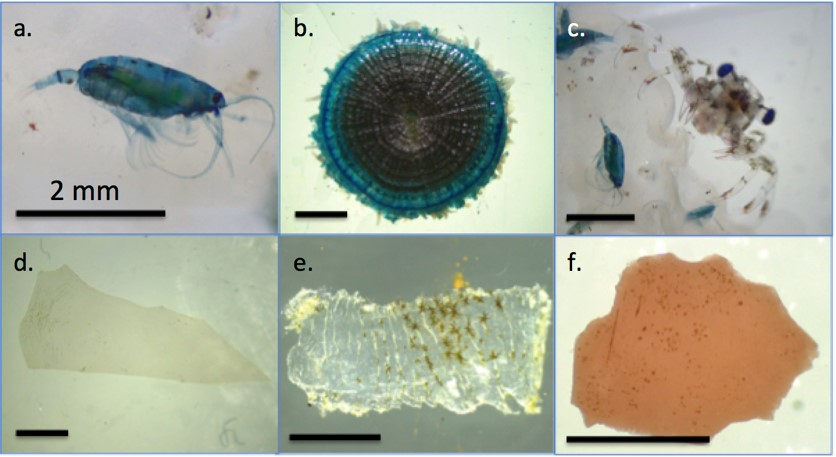

With the Manta Trawl net we are towing to collect plastic floating on the surface also collects many types of plankton, so we get a glimpse into this diverse and fascinating world. Thankfully along this cruise track, there have always been more plankton than plastic, and dominating all our net tows are the copepods, small crustaceans related to shrimp, and one of the most abundant types of animal on the planet. Some eat single celled algae, while others are predators eating whatever they can catch! Large ones are about the size of a grain of rice, and most that we have seen on this trip are a brilliant blue color.

Other prominent animals in our nets are Velella velella, or "By the wind sailors", small jellies with a sail on their back that drift with the wind, isopods and amphipods related to the "pill bugs" in your garden, and a small purple snail called Janthina that creates a bubble net at the surface to stay float. Janthina is a predator that feeds on Velella and other jellies at the surface.

We have seen some larger pieces of plastic including drink bottles, but most of what we see in our net is small broken fragments of plastic. Many have a thin slimy layer of attached bacteria and other microbes that we call the "Plastisphere", and this is one of the major topics we are studying on this voyage: Who are the members of the Plastisphere, what are they doing, and how do they affect the fate of plastic in the ocean? Are pieces of plastic transporting invasive species or potential pathogens around the ocean? Does the Plastisphere influence the ingestion of plastic by animals, the sinking rate of floating plastic, or the fragmentation of larger pieces?

Linda Amaral-Zettler

August 3 - Modelling microplastic transport

My name is Victor Onink and I am a Masters student from the Universiteit Utrecht in the Netherlands in Erik van Sebille's laboratory. I do Climate Physics, and for my Master thesis I modelled microplastic transport to determine physical processes behind microplastic accumulation in the subtropical ocean gyres.

Microplastic has been found in many different parts of the oceans, but that does not mean that the microplastic is distributed evenly everywhere. From observations we know that microplastic accumulates in "garbage patches" in the subtropical ocean gyres in each of the ocean basins. It is transported there by surface ocean currents, but there are several different physical processes that drive the surface currents such as wind, waves and surface level gradients. For my thesis I did Lagrangian modelling, where microplastic is represented by individual particles which are advected by the different surface component current fields. I found that the wind-driven currents are responsible for microplastic accumulation, but that wave-induced and surface level gradient currents play an important role in the final shape of the garbage patches.

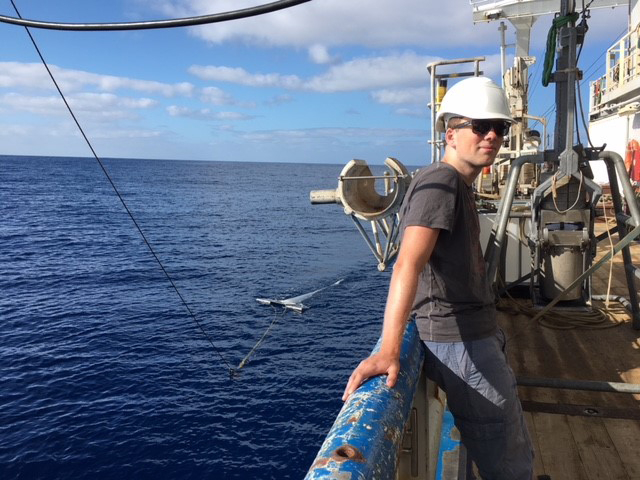

I can do a lot of interesting things with ocean modelling, but in the end, I am dependent on samples collected at sea to check whether my model predictions match up with reality. Therefore, I came along on this cruise to learn how these samples are taken. I have learned a lot already so far, such as how to collect and count microplastic collected with a manta trawl, how to measure water column properties with a CTD, and how to do different types of water sample filtrations. Now that we’re in the Mediterranean, I’m curious to see how the microplastic here is different from the North Atlantic.

Msc student Victor Onink, Utrecht University

August 2 - Microbial communities

Hello there! I am Vincenzo Donnarumma, a Masters student at the Stazione Zoologica "Anton Dohrn" in Naples, Italy with Prof. dr. Raffaella Casotti. Dr. Erik Zettler and Prof. dr. Linda Amaral-Zettler are external supervisors for my project. My field of research is also microplastics, more precisely I am interested in the microbial communities that live attached to these substrates. The main objective of my project is to study colonization of microplastics by microbes in the Gulf of Naples, considered a reference site for coastal areas impacted by anthropogenic activities.

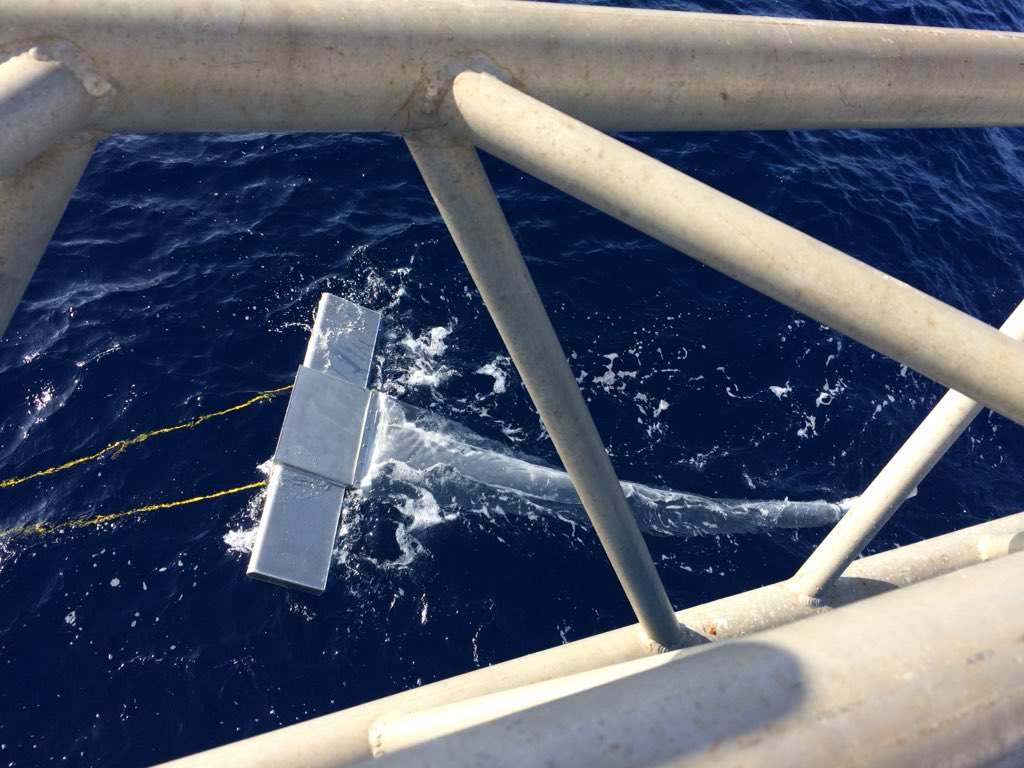

On this cruise I have been assisting with samples intended for characterizing the "Plastisphere". For microplastics there is a special neuston net, called a Manta Net, with special wings that help it float at the surface to concentrate plastic particles. After collection is complete, the net is rinsed and the pieces inside the cod-end are preserved for further analyses like DNA extraction and Scanning Electron Microscope visualization. This latter analysis will be carried out by me once I return to Italy.

What's it like on the RV Pelagia for the Microplastic Transit Cruise?

Well, it’s hard to explain, I will try. First, as a personal experience, for my first time in Atlantic waters and outside the Mediterranean coastal waters: looking at the Manta Net swimming there is just amazing. I am surrounded by experts in the field ready to help at any moment and by the next generation of scientists willing to give their time to assist with work beyond their own. Piece by piece I am figuring out how all our interests fit together and how everyone shares the goal of understanding the big threat that we are experiencing in the form of plastic marine debris. All this is encircled by the pleasant and professional RV Pelagia Crew always there to help, either with their experience on the ship or with their good company. All these ingredients make for the perfect recipe of a truly unforgettable experience.

Msc student Vicenzo Donnarumma, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples, Italy

p.s. talking about ingredients and recipies…the food is super good! And I am Italian so... ;)

August 1 - The Strait of Gibraltar

Early this morning we passed through the Strait of Gibraltar, but the cooler N. Atlantic water caused a thick fog that limited visibility, so we had only a brief glimpse of cliffs in Africa lit by the morning sun.

We’ve been very lucky with good weather, and the 9-person science team has settled into an efficient routine to accomplish our basic sampling plan. Our daily schedule includes a morning surface net (for plastic), an afternoon CTD/carousel to collect water samples and measure properties like salinity and temperature down to 1500m depth, and another surface net tow in the evening after supper. In addition, we are sampling continuously underway from the clean seawater system, and have collected 3 sediment samples using a box corer when we find water less than 1000m deep. In addition to their own research, everybody has cross-trained so they are able to help out with all of tasks necessary to deploy the equipment and recover and process the samples (including a LOT of filtering!). We are generally busy from after breakfast to around 21:00, at which time we gather on deck to enjoy the setting sun, then play cards or read till we go to sleep to begin again the next morning.

I’ve sailed on a variety of research vessels over the last 30+ years, and I am very impressed with the comfort, scientific capabilities, and crew support aboard Pelagia. The fixed wet and dry laboratories are laid out well and the container labs provide additional space and isolated work areas that can be customized for individual projects. We are using one container for culturing bacteria, one for testing new instrumentation to detect plastic in seawater, and one for filtering pigments, DNA, and plastic microfibers. The professional crew is contributing to the research by handling the ship, safely deploying our sampling equipment, providing advice and help to improve the way we are sampling, and improvising to fix things that break or don’t work as expected. They are always asking how they can help and are very interested in the science and research we are doing. Of course food is extremely important aboard, and galley is providing amazingly good meals so none of us are going hungry or losing any weight on this trip!

Erik Zettler

July 31 - Phytoplankton

My name is Alexandre Epinoux and I am a Ph.D. student at the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples, Italy with Prof. dr. Raffaella Casotti. I am interested in marine microbiology and ecology, and am focusing right now on phytoplankton – floating single cells capable of producing their own food through photosynthesis.

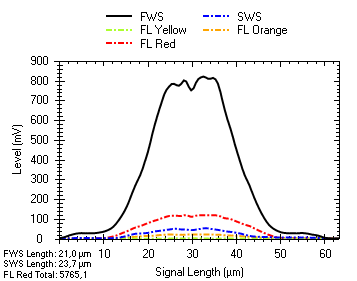

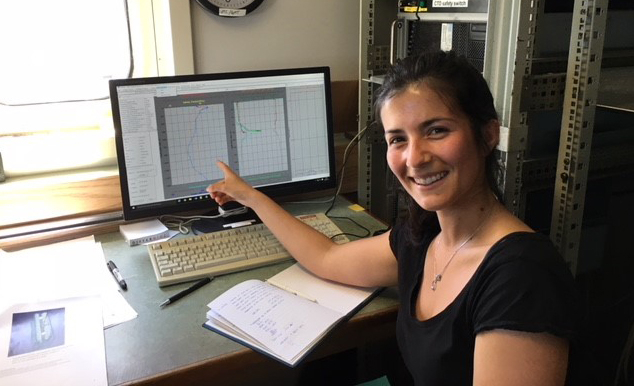

Quite little is known about what drives their abundances on a short spatial and temporal scales, although those cells are crucial to us: they ensure more than 50% of the world’s photosynthesis. That's the oxygen in every other breath of air you take! Using a specially designed flow cytometer to count thousands of cells and record each unique optical signature continuously, I am able to estimate the concentration of the different groups making up the phytoplankton world. With this instrument, I can accurately analyze cells as small as 1 µm and as big as 800 µm – which is the equivalent of working on a size range going from a man to twice the Eiffel tower!

Quite little is known about what drives their abundances on a short spatial and temporal scales, although those cells are crucial to us: they ensure more than 50% of the world’s photosynthesis. That's the oxygen in every other breath of air you take! Using a specially designed flow cytometer to count thousands of cells and record each unique optical signature continuously, I am able to estimate the concentration of the different groups making up the phytoplankton world. With this instrument, I can accurately analyze cells as small as 1 µm and as big as 800 µm – which is the equivalent of working on a size range going from a man to twice the Eiffel tower!

This scientific cruise is an opportunity for me to use this flow cytometer for a long duration and to collect data regarding the open ocean, something I do not have access to easily from Naples! On the Pelagia, my instrument is running continuously, linked directly to its surface pump. This allows me to provide almost real-time information about the concentrations of the different phytoplankton groups at the surface along the cruise track from the Azores to Sicily. Additionally, I also analyze the water collected below the surface. In the end, those data will be coupled to other physico-chemical analysis, and in particular microplastic content in the water: this shall give us a first idea of the impact of plastics on phytoplankton ecology.

PhD-student Alexandre Epinoux, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples, Italy

July 30 - Marine debris and microplastic pollution

I am a marine biologist that lives on the beautiful islands of the Azores Archipelago. I became interested in marine debris and microplastic pollution in the Azores the day I noticed dolphins playing with a plastic bag in the pristine waters of Pico Island. Then while walking along the beach in Porto Pim (Faial Island) back in 2011, I noticed very small colored particles along the tidemark: they were tiny little plastic fragments and resin pellets, so many I couldn’t hold them all in my hands. I was about to start my Master’s at that time and decided that marine debris in the Azores Archipelago is where I really wanted to focus my studies.

Since 2012 I have been working on coastal marine debris presence, microplastics presence in the ocean, and their vertical distribution in the water column. I have been collecting data on beaches to understand what type of marine debris is present, how it varies in time and space and throughout sampling seasons, what local and distant sources affect its presence, how the problem is affecting the Azores, and how we can possibly reduce it at a local scale.

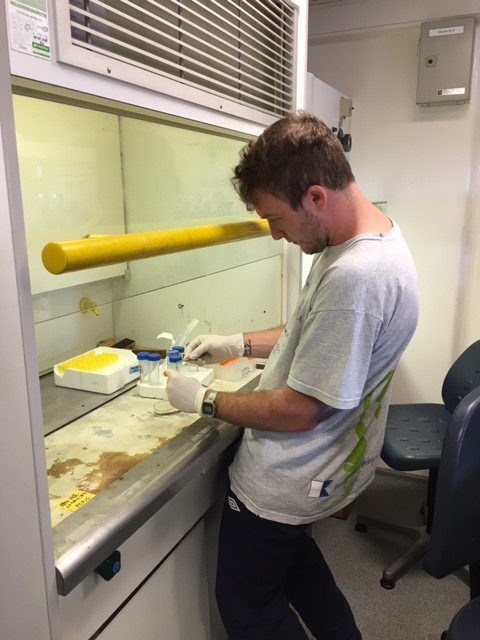

Being on board NIOZ’s RV Pelagia and participating in the PE442 Microplastics cruise is allowing me to study and sample microplastics not only in the Azores, but also the Mediterranean. On this cruise I have been able to collect water samples to investigate microplastics presence in the water column from the sea surface to the deep sea. After the "hydrocast" comes back on deck, many other procedures take place including filtration, counting and particle identification. I have been lucky to have team members that help me through the whole process, which allows me to collect samples the best way possible and to contribute with one dataset among so many others that take place on this cruise. For that, I am truly grateful.

PhD-student Catharina Pieper, Universidade dos Açores

July 29 - MantaRay

My name is Ethan Edson and I am a Scientist from Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, USA collaborating with Dr. Linda Amaral-Zettler. My research involves creating novel technologies to help us better sample microplastics and other water quality parameters in real time.

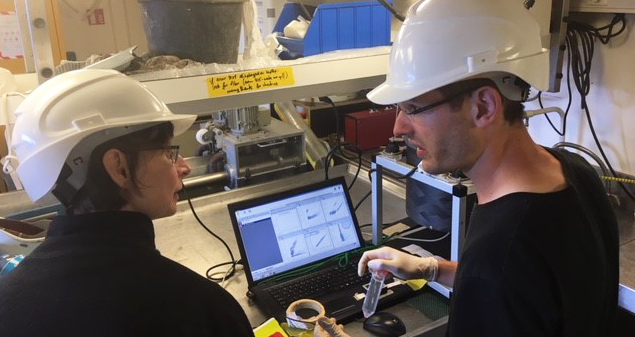

I am joining this cruise with a piece of equipment I designed and built called MantaRay, a bench-top flow through instrument that analyzes and images microplastics in complex water samples. The goal of MantaRay is to reduce the labor involved with detecting microplastics in seawater samples and to help create a tool that can be used by researchers to analyze the concentration, size distribution, and chemical composition of microplastic particles in situ.

During this cruise, I will be testing new onboard particle analysis software, capturing data from a flow through system onboard, and helping to better optimize the system to sample more efficiently in future deployments. I am looking forward to working with the other scientists onboard this cruise to see how data collected from MantaRay fits into the bigger picture of the other studies taking place! Stay tuned for more.

Ethan Edson, Northeastern University Boston

July 28 - Degrading effects of UV radiation on materials and development of novel methods to quantify these effects

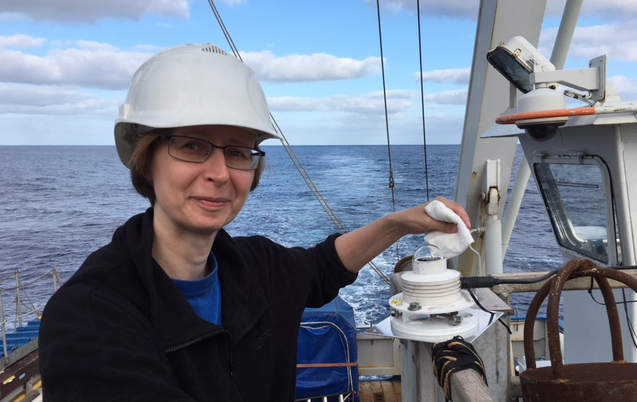

My name is Anu Heikkilä. I’m a physicist, and I work for the Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI) as a senior research scientist. My background is in molecular physics, but my work at the FMI has focused on solar and artificial UV radiation and the effects of UV radiation. My special area of expertise is degrading effects of UV radiation on materials and development of novel methods to quantify these effects.

While participating in the microplastic transit of RV Pelagia, I'm measuring solar ultraviolet (UV) radiation and solar global radiation with carefully characterized instruments onboard the vessel. The measurements yield in situ data on the UV and global solar radiation conditions on the stop-on stations along the route of the vessel. These data supplemented with satellite derived radiation data may be used when studying the fate of plastics in the oceans. UV radiation has been identified as a key component in the break-down of secondary microplastics that are derived from larger plastic debris items, especially on the beaches and surface waters.

Working with the research team of Dr. Linda Amaral-Zettler gives me a great opportunity to learn about the approaches and methods of marine scientists. I’m very much looking forward to exploring the field, discovering new fascinating things, identifying knowledge gaps where I could help with my expertise, and making a contribution in the efforts to find solutions to one of the most alarming environmental problems of today.

Dr. Anu Heikkilä, Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI)

July 27 - The fate of biodegradable plastics in marine environments

Half a year ago, I started my PhD at NIOZ, Texel, and my research topic is about the fate of biodegradable plastics in marine environments and about the microorganisms involved in this. Even before I arrived at NIOZ, my supervisor Prof. Linda Amaral-Zettler made me block the 25th of July until the 9th of August in my agenda. It was for my first research cruise with the theme being microplastics in our environment.

For my first cruise, the route is not that bad I must say: Terceira (the Azores, Portugal) to Sicily (Italy). Nice timing also, since I am escaping from the very high temperatures currently in the Netherlands. After a day of discovering the surroundings of the starting point of our trip, yesterday we set sail with the Pelagia. Although it is my first time on a research cruise I am getting used quite fast to the rolling of the ship and performing research and experiments underway. I think my fellow researchers are getting set up quite good as well. They, the friendly crew and the nice food make the journey also quite pleasant.

Although plastics can be labeled as (marine) biodegradable, testing these plastics is not always done in very realistic environmental simulations and also investigating which microorganisms are involved in this process is very limited usually. I will hopefully gain a lot more insight into the biodegradation process in various marine settings during my PhD.

Back at NIOZ all samples will be processed and hopefully we will then find some unique biodegrading microbes. Meanwhile, during the cruise I will also learn a lot more from the other research performed on the ship, which you will read about later. In any case, experiencing this cruise was and will be unforgettable.

NIOZ PhD student Fons de Vogel (Utrecht University)

July 26 - Departure

Today was a day of many firsts for RV Pelagia cruise 442: my first time as Chief Scientist, many of our first times on the R/V Pelagia vessel and also a first time to be heading east across the Atlantic instead of west (for me). We departed the Azorean island of Terceira about 1530 today (July 26th) and spent the better part of the morning unpacking equipment and supplies needed for this transit cruise that we've named the "Microplastics Transit Cruise". As such we are preparing a journey into the Anthropocene over the next 12 days starting at Praia de Vitoria and ending in Catania, Sicily (see Image of Fons and Erik at Schiphol). We will be using a collection of traditional and more technology-driven techniques to better understand the impacts of Plastic Marine Debris (PMD) in the marine environment and their associated surroundings.

Linda Amaral-Zettler