Deep sea microbes can adapt their basic building blocks

Every microbe uses the element phosphorus to build its outer protective layer. Just like all cells in our human body. But what if there is almost no phosphorus available, which is the case in some areas of the deep sea? An international team lead by NIOZ microbiologists have now shown that those microbes know how to replace a lack of phosphorus with other elements that are present, such as sulphur and nitrogen. This provides clues as to how marine life can adapt to changing ocean conditions.

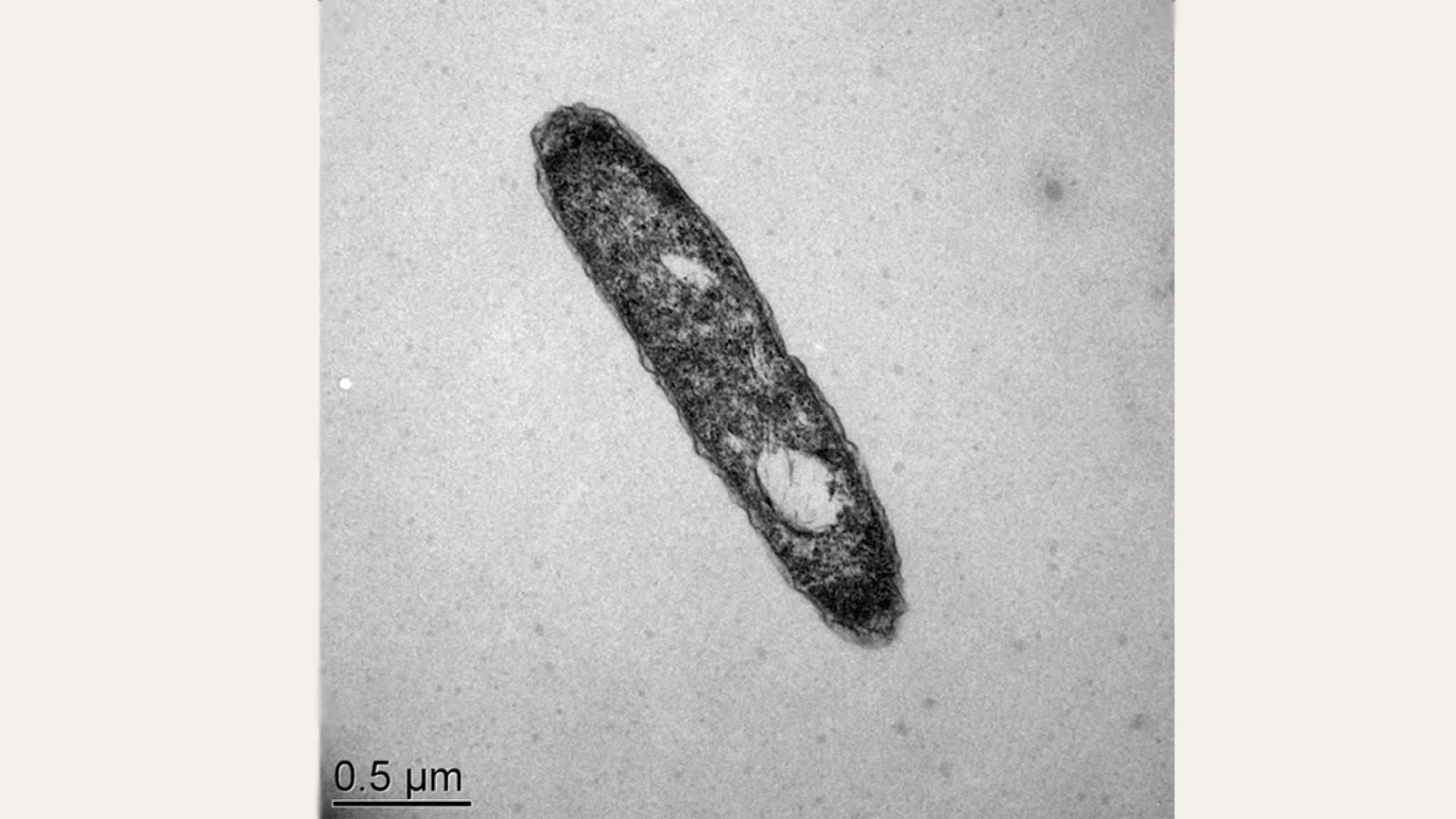

A microscopic image of the deap sea microbe Desulfatibacillum alkenivorans. (photo: Su Ding)

Microbes are organisms so small, you can’t see them with the naked eye. Many types of microbes consist of only one cell: think of bacteria that can cause an infection, but also the microbes that live in your gut and keep you healthy. Every microbe has a membrane that functions as a kind of 'skin'. The membrane provides the microbial cell's structure, protects its interior and regulates which substances enter and leave the cell. This membrane usually consists of phospholipids: ‘tails’ of fatty acids with a ‘head group’ containing the element phosphorus(see image). So phosphorus is essential for building the membrane of every cell. It also plays a major role as a component of DNA and in the energy management of cells.

Working like a complex factory

To their surprise, in the near absence of phosphorus the bacterium was found to replace almost all the phospholipids in its membrane with novel lipids containing sulphur and nitrogen, elements which were available. "Apparently, this microbe is capable of adjusting the chemical composition of the cell’s membrane, so it can save the scarce phosphorus for even more essential cell ingredients such as DNA," explained NIOZ principal researcher Su Ding. "This change from phospholipids to sulphur and nitrogen lipids requires a huge coordinated adjustment of the whole cell system,” adds Jaap Sinnighe Damsté, supervisor of the research project. “It shows that such tiny microbes are actually working as a very complex factory."

Adjusting lipids to temperature

Ding and his colleagues also saw that a change in temperature caused the bacterium to change the composition of its lipid membrane. "This means that this bacterium found an entirely new way to adapt to difficult conditions," says Ding. This is relevant information: ocean warming and human activity – such as fish farms - can cause surpluses or shortages of nutrients. "Understanding better how bacteria adapt to these situations, can help us with strategies to counteract their unwanted effects on marine life. And by extension, also protect people and societies that depend on the sea for their livelihoods."

Unique technology

The research team used a unique technique to analyse the lipid membrane of the bacteria, developed at NIOZ a few years ago. This lipidomics method has a very high sensitivity and allowed the researchers, for the very first time, to analyse over 400 new lipids present in the bacterium, including those new nitrogen and sulphur lipids that replaced the phospholipids. The NIOZ laboratory is one in three laboratories worldwide that currently applies this technology. Earlier this year, they used this technology to uncover that parasitic archaea can be very picky eaters.