Foraminifers: the smallest organisms drive the biggest processes

The increasing amount of CO2 we are pumping into the atmosphere causes ocean acidification. That could pose a serious problem for calcifying organisms, such as shellfish and corals. And for foraminifers, but they appear to have their own solution to this problem, Lennart de Nooijer and colleagues write in Science Advances. “These unicellular organisms can adjust the acidity in and around their cells, to keep on building their shells.”

Half of all the chalk in the ocean

Foraminifers are single-celled organisms, not bacteria but protists, that form the most photogenic calcium shells. The largest can grow more than a centimeter across, but most are about the size of a grain of sand. With these countless 'calcium carbonate skeletons’ together, foraminifers are responsible for roughly half of all the chalk made in the ocean. And that's important because calcification is an important part of the global carbon cycle.

With the increasing amount of CO2 in our atmosphere, and therefore in the ocean, the water is becoming slightly more acidic. With that, according to the laws of chemistry, forming a shell should become slightly more difficult. But foraminifers appear to be able to evade that law. “These single-celled organisms can adjust the acidity in and around their cell so that chalk formation still remains possible,” says Lennart de Nooijer of the Ocean Systems Department.

A graph depicting the so called 'sources’ en ‘sinks’ for carbon, above and under the horizontal line. (Photo: Friedlingstein et al. (2023))

CO2 makes water acidic, because:

CO2 in ocean water (H2O), gives HCO3- and H+. And H+ = acid!

The amount of H+ is inversely proportional to pH:

more H+ = lower pH = more acidic.

less H+ = higher pH = more alkaline

Lime dissolves with acid

Anyone who has ever had to descale a kettle or an espresso machine knows: precipitated chalk dissolves in acid, like in a dash of vinegar. So, the notion that ocean acidification (due to increases in CO2) is troublesome for calcifying organisms such as shellfish, coral polyps and, consequently, foraminifers, is obvious. "The problem is: it just doesn't quite add up", says De Nooijer.

Acid dissolves chalk, because:

chalk (CaCO3) plus acid (1 H+) makes Ca2+ and HCO3-

Foraminifers create their own environment

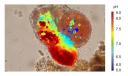

By looking at foraminifers with a laser and using fluorescence microscopy, De Nooijer and colleagues were able to see how these single-celled organisms create their own chemical environment. De Nooijer: "They are able to slightly raise the pH in their cell and thus create an alkaline environment locally. That means they can counter the acidification of the ocean water a little bit and keep on forming their shells."

A microcopic image of a foraminifer, with colours depicting the pH values.

Nice for the foraminifers, not for the acidic ocean

The fact that foraminifers can just keep sequestering calcium carbonate despite the acidifying ocean water is nice for those single-celled organisms, but not necessarily for the ocean environment, says De Nooijer. "When they calcify, a little bit of the dissolved carbon is released again in the form of CO2. So, organisms that form shells and skeletons of calcium carbonate are themselves contributing to the acidification of the environment."

When making chalk (CaCO3), organisms introduce additional CO2 into the water because:

2 parts HCO3- plus 1 part Ca2+ makes CaCO3, CO2 and H2O

Large role for tiny organisms

All in all, foraminifers play a central but also complex role in the bookkeeping of oceanic carbon (and thus CO2) in the oceans, De Nooijer emphasizes. "Depending on whom you ask, either foraminifers or another group of unicellular organisms, the coccolithophores, will play the most important role in permanently sequestering carbon in the oceans, and thus in ‘neutralizing’ CO2 from the atmosphere. Roughly speaking, these organisms together each take up half of the carbon sequestration. This means that all those other calcifying organisms, such as shellfish or coral polyps do not make a dent. They are unimaginably important for biodiversity, but not for carbon sequestration", De Nooijer says.

Fossil foraminifers tell interesting stories

The fact that foraminifers are still producing shells despite an acidifying environment really should not have come as a surprise, De Nooijer argues. "Just look at the famous cliffs of Normandy and Dover. Those were once formed in the geological period of the Cretaceous, up to 65 million years ago. During that period, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere was often a lot higher than today. But apparently all marine organisms were still able to form lime in a more acidic sea."

De Nooijer therefore emphasizes that fossil foraminifers can still teach us a lot about carbon and climate. "These organisms not only store calcium and carbon in their shells, but also other minerals, such as magnesium. The amount of magnesium depends on the temperature at the time of calcium formation. Therefore, by studying fossil foraminifers down to the atomic level, we can infer what the temperature was at the time of capture. We have models to roughly predict how much CO2 will lead to what rise in temperature, but those models are still far from accurate. Studying foraminifers can further refine those models."

Smallest organisms explain biggest processes

De Nooijer emphasizes that we will never properly understand the biggest processes on Earth, such as planetary climate change, without knowing the very smallest organisms such as foraminifers. "The amount of carbon these unicellular organisms sequester in the form of lime and thus: the amount of CO2 they remove from the atmosphere is immense. They have a central place in the carbon cycle and thus in our climate problem."